March 2nd

Most of our knowledge of Saint Chad comes from a single impressive source, Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People. The Venerable Bede, often called ‘The Father of English History’ was born in the year of Saint Chad’s death and was himself a pupil of Trumbert, one of Saint Chad’s pupils who, he says, “instructed me in the scriptures and had been bred in his monastery and under his direction”.

Saint Chad was one of three brothers born in Northumbria, possibly of a noble family in the 620’s. The name ‘Chad’ is Celtic rather than Saxon in origin but nothing is known of his background. The brothers were educated at the monastery on Lindisfarne under Saint Aidan. The religion practised here was the Celtic form of Christianity that had been introduced into Britain in the 3rd and 4th centuries, probably from Gaul. It differed in many forms from that introduced into England by St. Augustine and his followers at the end of the 6th century. There were technical differences over the dating of Easter and the shape of the tonsure, but, more important, it advocated a strict type of monasticism derived from that followed in the Egyptian deserts by the earliest Christian monks. Saint Columba founded the most celebrated of these Celtic monasteries in Britain on the island of Iona in 563, but the largest was that at Bangor Iscoed which was destroyed in 616. The monastery on Lindisfarne had been set up by Saint Aidan, one of the monks from Iona, at the invitation of King Oswald of Northumbria.

The Celtic liturgy Chad would have known at Lindisfarne differed from that of Rome: the scanty evidence we have suggests that it was derived from the Gallican rite and was more closely related to Eastern liturgy. The best evidence we have is the Stowe Missal that dates from the eighth century, the same period as the St Chad Gospels at Lichfield. Distinctive Eastern features of this rite are the litany between the epistle and gospel, the absence of the ‘filioque’ clause from the Creed and the inclusion of an ‘epiklesis’ (invocation of the Holy Spirit) in the eucharistic prayer. We are told that the Picts were greatly impressed by Columba and his monks singing an early form of chant that was probably similar to the Byzantine style of chant used in Gaul. Gregorian chant was only later introduced into Britain by Saint Augustine’s Roman mission at the instance of Pope Gregory. It was at Lindisfarne that Saint Aidan started a school for twelve boys that included Chad and his three brothers Cedd, Cynebil and Caelin. Here with the other pupils they must have learnt to chant the psalms and read Latin. Eventually Chad and some of the others were sent to a monastery in Ireland where it is said that he was “constantly occupied in prayer, fasting, and meditation of the sacred scriptures” and here he became a priest.

Subsequently Cedd was raised to the rank of bishop as he worked to establish Celtic monasteries among the East Saxons. However his name is mostly remembered for founding a monastery at Lastingham on the desolate Yorkshire moors where he along with his brother Cynebil and the other monks and many clergy fell victim to plague in 664, only one small boy survived by the intercession of Chad. In response to Cedd’s dying wish Chad succeeded him as abbot.

The Roman mission, led by Saint Augustine who had established his see at Canterbury, was gaining force and the conflict between Celtic and Roman practices famously came to a head earlier in the year 663/4 at the Synod of Whitby. The case for the Roman observance was forcefully put by Wilfred who, although educated in the Celtic tradition at Lindisfarne, had been converted to the Roman position as a result of his travels on the continent and time spent in Rome. The result was the decision to abandon the irregular Celtic customs such as the archaic system for dating Easter, the shape of the tonsure and the rules for consecrating bishops. However the often-overstated problems presented by this decision did not result in any impediment to the appointment of Chad to the see of York in the absence of the former bishop, Wilfred.

The difficult situation following the Synod of Whitby was compounded by the bubonic plague, which came from Asia and swept Western Europe in the summers of 663 and 664. In addition to Cedd and the community at Lastingham there died, not only Tuda of Lindisfarne, but also both Deusdedit, Archbishop of Canterbury and his designated successor Wighard before his consecration. Meanwhile Wilfred had been consecrated with much splendour to the see of York at Compiègne in Gaul to avoid the Celtic rite, the validity of which he considered to be dubious.

This confused situation was one of the problems to be resolved by the newly consecrated Archbishop of Canterbury, Theodore of Tarsus, a highly respected Eastern Orthodox monk and scholar aged 67. Saint Chad’s consecration to the see of York during the five-year interregnum at Canterbury by Wini, bishop of the West Saxons and two Celtic bishops was deemed to be irregular whereupon Chad immediately gave way, we are told, with great humility saying that he had never considered himself worthy to hold the position. Wilfred took his place at York and Chad returned to his monastery at Lastingham.

The consolidation of the church in England into a centralized diocesan system owing obedience to Rome via Canterbury and regulated by a synodical system was the work of Archbishop Theodore. Thus the rites they followed, the Roman calculation of the date of Easter and even the music were conformed to the use of Rome. In order to ensure that Theodore did not introduce any Eastern influence, Pope Vitalian sent with him a representative called Hadrian, a formidably learned abbot from North Africa. It was at the request of King Wulfhere of Mercia in 669 that the archbishop, impressed by the humility with which Chad had acted over the bishopric of York, recalled him from his monastery at Lastingham to be Bishop of Lichfield. Theodore re-consecrated him conditionally according to the Roman rite and insisted that Chad must abandon the Celtic custom of visiting his diocese of foot. We are told that when Chad remonstrated, the archbishop himself forcibly lifted him on to a horse.

According to Bede, the choice of Lichfield as the site of the principal Mercian bishopric was Chad’s while Eddius Stephanus, Wilfred’s biographer, says that the choice was Wilfred’s. Whoever made the choice is of no real importance; the site of Chad’s first cathedral was at Stowe at the eastern end of the Minster pools. It was here, probably an island surrounded by marshes at the time that, in the Celtic fashion, Chad found a site that corresponded as closely as possible in Mercia to Lindisfarne or Iona. Bede tells us that the site was near the church and the late Professor Finberg suggested that Chad’s oratory might have been situated high above Stowe and the cathedral in, what is now, the churchyard of St. Michael’s on Greenhill. We know that one member of the familia of seven or eight brothers was Owini who had served Queen Aethelreda as chamberlain with great distinction, had become a monk at Lastingham with Chad and came with him to Lichfield. Having no aptitude for study Owini had offered himself as a postulant holding an axe and a hatchet proffering his manual work instead.

Near Chad’s oratory was a pool formed by a natural spring. It was described in the sixteenth century by Leland as “a spring of pure water, where is seen a stone at the bottom of it, on which, some saye, S. Chadd was wont to stand in the water and pray.” This was an ascetic practice particularly associated with Celtic monasticism. The pool was used for baptism as well as to provide water. Today Saint Chad’s Well is to be found in the churchyard at Stowe on the north side of Lichfield town centre, on the northern edge of Stowe Pool. Legend has it that on one occasion a breathless hart sprung out from the forest and began to drink from the well before disappearing back into the forest. However, Wulfhade, son of Wulfhere, King of Mercia, was hunting the hart. Chad then prayed for the return of the hart, which emerged from the forest. Wulfhade amazed by this begged for immediate baptism for him and his brother Rufine. On discovering his sons had become Christian Wulfhere had them murdered. Then in a fit of remorse, he hurried to Chad’s cell where he found the saint in prayer surrounded by heavenly light. Chad rose and hung his vestments on a sunbeam. Chad accepted Wulfhere’s remorse and as penance bade him to tear down all the heathen shrines and replace them with monasteries.

One of these was at Peterborough where this legend was preserved. Whatever the truth behind the legend the extent of Chad’s influence is impressive considering the very short period of his bishopric, less than three years. Bede records Owini’s account of Chad’s death on

March 2nd 672. About a week before, while working outside Chad’s oratory, Owini heard “a sweet sound of singing and rejoicing descend from heaven to earth” coming from the direction of the winter sunrise in the south-east and enter the bishop’s oratory where Chad was praying alone. When the singing had ended Chad summoned the astonished Owini and told him to assemble the other seven monks. Chad told them that he was about to die and urged them to live together in love and peace in the monastic discipline he had taught them. He asked Owini not to speak of the angelic choir until after his death and on March 2nd 672 Chad “departed to the joys of heaven” with the sacrament on his lips. Bede also recounts another witness who said “he saw the soul of his brother Cedd, with a company of angels, descending from heaven, who, having taken Ceadda’s (Chad’s) soul along with them, returned again to the heavenly kingdom”.

Saint Chad has been well described by C. J. Godfrey in The Church in Anglo-Saxon England, “Chad was a man who lived close to heaven, in daily expectation of death. He heard the voice of God in the wind. Angels were his familiar companions.” Bede, despite his pro-Roman disposition, gives Chad high praise for his merits as a teacher, for his humility, devotion and

poverty as a monk, and his wisdom as Bishop of Mercia. The body of Saint Chad was first buried in Saint Mary’s Church where miracles of healing were soon being reported at his shrine and Bede reports the deliverance of a man from mental infirmity. In 700 Bishop Headda built a new cathedral dedicated to Saint Peter and translated the relics to a shrine described as “a wooden monument, made like a little house, covered, having a hole in the wall, through which those that go thither for devotion are wont to put in their hand and take out some of the dust. A Norman cathedral made from stone replaced the wooden Saxon church, and this was in turn was replaced by the present cathedral begun in 1195. The shrine of Saint Chad was a popular place of pilgrimage and Bishop Walter de Langton was responsible for building an elaborate and vastly expensive marble shrine adorned with gold and precious stones to the east of the High Altar. At the Reformation the shrine was initially spared, at the intercession of Bishop Robert Lee, but it was later completely destroyed. Some fragments of the relics of Saint Chad were rescued and they are now to be found in the Roman Catholic Cathedral at Birmingham. Recently a radio carbon test has dated them to the seventh century

and still more recently, in February 2003, an eighth century sculpted panel of the Archangel Gabriel was discovered under the nave of Lichfield Cathedral. The 600mm tall panel is carved from limestone, and originally was part of a stone chest, which is thought to have contained the relics of St Chad. The panel was broken into three parts but was still otherwise intact and had traces of red pigment from the period. The pigments on the ‘Lichfield Angel’ correspond

closely to those of the Saint Chad Gospels, which have been dated to around 730. The Angel

was first unveiled to the public in 2006 and is now on permanent display in the chapter house.

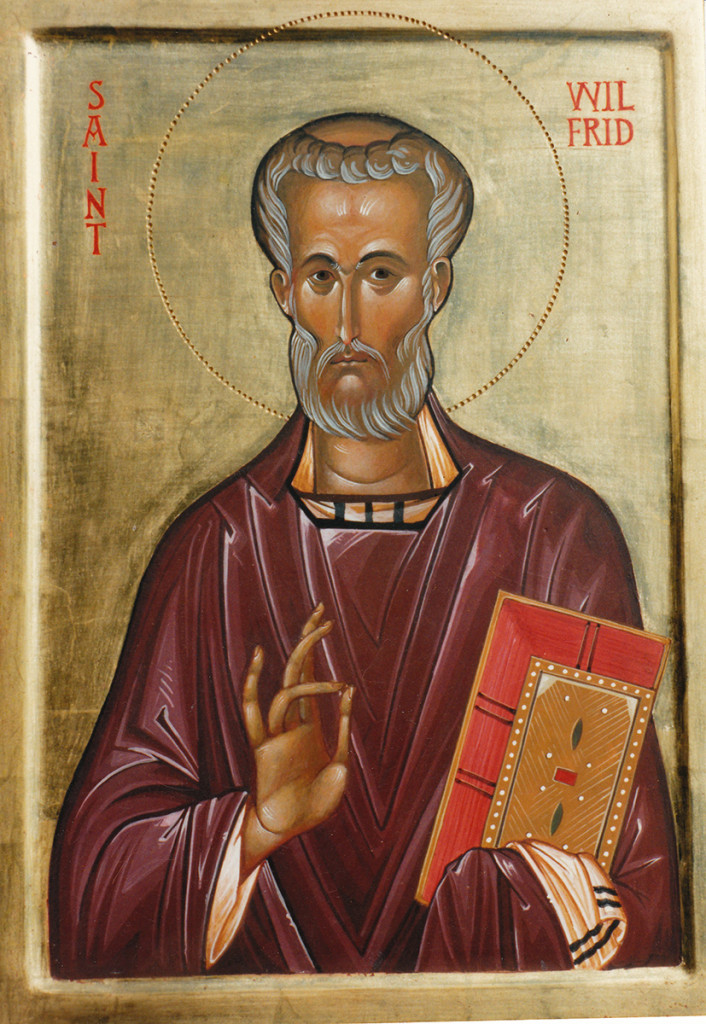

To the east of the High Altar is the site of the despoiled shrine of Saint Chad on which a beautiful icon of Saint Chad, written by Orthodox iconographer Aidan Hart, now stands. Today Saint Chad is acknowledged as a great and holy saint throughout all the major branches of the Church. The Eastern Orthodox Church holds him in particular veneration because, as a pre-schism saint in the Celtic tradition of Iona and Lindisfarne, he had close affinity to the

eastern tradition. The eleventh century Shropshire born historian, Ordericus Vitalis observed that the bishops of the Celtic Church were all monks, which is still the Orthodox practice.

There are over thirty churches dedicated to Saint Chad, mostly in the old kingdom of Mercia and many dating to Saxon times. Many place names are toponyms that are said to have associations with Saint Chad. Some famous ones are Chadkirk, Cheadle, Cheddleton and even Kidderminster, but there are some lesser-known ones like Cadney in Lincolnshire and Hanmer in North East Wales that in the Domesday Book is simply called “St. Chad’s”. Within a mile or so are to be found some curiously suggestive names, possibly indicating a local cultus. Within the ancient parish is another Cadney (Chad’s island?) and nearby is the Gospel Meadow in which is the Gospel Pool. Less than a mile to the north is Llys Beddyd (lake of Baptism) (see photograph below), Eglwys Cross (‘Church Cross’) and a few hundred yards from the parish church of Saint Chad a holy well existed until recently (see photograph below). Then to the southwest, in Hampton’s Wood is a fine timber-framed medieval Bishop’s House and not far distant at Welshampton there were two ‘Gospel Hathornes’. Leaving aside the colourful speculations of a nineteenth century antiquarian cleric, none of this can be substantially dated back to Saint Chad, however it does seem to show the lasting influence of Saint Chad’s short time in office as Bishop of Lichfield and the veneration in which he was held in this area. Alan Thacker has shown an interesting and relevant correlation between episcopal estates and early dedications to Saint Chad in the north-west midlands. Another instance is that the oldest church in Shrewsbury built on a hill within a loop of the Severn which, at that time must have almost been an island and was dedicated to Saint Chad, was characteristic of a Celtic monastic settlement. To the south of Shrewsbury is the unique dedication to another of Saint Aidan’s Lindisfarne scholars, Saint Eata, on the bank of the Severn at Atcham. Still further south near Newport there is Chetwynd that claims to be ‘Chad’s Way’ and to the south is ‘Chadwell’. Yet another connection is Saint Milburga, the Saxon owner of Sutton, who had been drawn to Much Wenlock by the example of the saintly life of Owini, who had settled there as a hermit after the death of Chad. There was a hermitage at Sutton, part of Saint Milburga’s estate, in the medieval period and today the Orthodox Church owns the medieval church, built there by the monks of Wenlock, where Saint Chad of Lichfield is venerated among the saints. His feast day is observed on March 2nd in both the Eastern and Western traditions.

Christopher Jobson

The Feast of Saint Chad, 2012