Commemorated on 3 February

Werburgh[1], a princess of Mercia, exchanged her coronet for a veil early in life and became a great foundress and leader of monastic communities in East Anglia and Mercia. Her greatness in life is reflected in her veneration in death. Her holy body, jealously guarded by her monastic community in Triccingham, was given up through a miracle when the locks fell away and she was borne by monks to Hanbury, her desired resting place. But it was Aethelflaed – Lady of the Mercians – who most likely delivered her relics to Chester – the city of her patronage – and established her veneration in Shrewsbury. In Chester she delivered the city from fire and perils inflicted by barbarian invaders. In Shrewsbury her veneration was joined with that of the royal saints Alchmund and Milburga to offer the town protection against the heathen Viking invaders. Her chapel in Shrewsbury is long gone but her memory has been recently restored. She now joins other local saints on the walls of the Orthodox Church of the 318 Godbearing Fathers of the First Ecumenical Council, Shrewsbury in a beautiful roundels by master iconographer Aidan Hart. She helps unite the community in renewed veneration. The British who have found a home in Orthodoxy honour her as a predecessor linking them to the undivided Church in these lands. The people who have settled here with roots in traditional Orthodox countries now adopt her as a local patron as her way of life mirrors that of their own saints from the East.

The roundels represent ichnographically the words of the Epistle to the Hebrews, seeing we also are compassed about with so great a cloud of witnesses.[2] The reason for the inclusion of an Icon of Saint Werburgh in this collection of roundels is uncovered in this history of the saint. The history of the saint is complex and diverse and the sources are collected and presented here as an offering to accompany the iconography so that her memory can be honoured as is due.

Saint Werburgh, for centuries venerated as the patroness of Chester, was not born there, neither did she live, die or was buried there. Werburgh was the daughter of King Wulfhere the first Christian king of Mercia (657–75) and his wife Eormenhild, and through her mother was related to both the Kentish and East Anglian royal families. She early showed an aptitude towards the religious life and entered the monastery of Ely where her great aunt Aethelthryth was abbess. As the “Te Deum” was chanted Werburgh entered the cloister with Aethelthryth. Werburgh was stripped of her costly apparel, she exchanged her coronet for a veil, and in a rough habit began her new life.

Werburgh remained for some time at Ely. She succeeded her grandmother Seaxburh and her mother Eormenhild as abbess of the double monastery, but was recalled to Mercia by her uncle, King Aethelred, Wulfhere’s brother and successor (675–704), and given authority over the nunneries of his kingdom.

Werburgh’s work was deeply rooted in prayer and discipline, taking but one meal daily and that only of the coarsest food following the example of the desert fathers she recited the whole of the Psalter daily upon her knees.

She performed miracles while living on her father’s estate at Weedon (Northants) and died about 700 in her monastery of Triccingham (thought by some to be Trentham but almost certainly Threekingham, Lincs[3]).

A few years later she was buried in accordance with her wishes in the monastery of Hanbury, near Repton (Staffs.). Nine years later, in recognition of her sanctity, her remains were raised at the command of her cousin, the Mercian king Ceolred (709–16), and were found to be incorrupt. Her relics remained enshrined at Hanbury until the time of the Danish invasions, shortly after which they were removed to Chester where they remained until the destruction of her shrine in the 1530s[4].

The earliest account of her life was given by Goscelin, a Flemish Benedictine monk who came to England with Hermann, Bishop of Salisbury, probably in 1053. He gathered material from all over the kingdom, writing the lives of the English saints as he travelled, finally settling at Canterbury. Although the authenticity of Goscelin’s work has been questioned in recent times the research of Professor Rosalind Love supports it[5]. It gives an account of wild geese that damage the saint’s crops on her royal estate at Weedon but are made to repent and one of them was miraculously restored by Werburgh.

There are brief notices of the saint in a number of 12th-century century sources, including John of Worcester’s Chronicle, Symeon of Durham, Henry of Huntingdon’s Historia and William of Malmesbury’s Gesta pontificum. Other traditions about Werburgh and her relics are related in the 12th-century history of the abbey of Ely (the Liber Eliensis), and in the Latin Lives and lections of Eormenhild and Seaxburh[6]. More substantial accounts are given by two monks of the Benedictine Abbey at Chester, which was named after the saint: Ranulf Higden, in the early fourteenth century in his Polychronicon and lastly Henry Bradshaw, in the sixteenth century wrote, “The Holy Lyfe and History of Saynt Werburge, very frutefull for all Christen people to rede.” Furthermore Saint Werburgh is mentioned in various late Anglo-Saxon lists of the resting-places of English saints and in a number of 11th- and 12th-century calendars and she is represented in numerous ancient parish church dedications.[7]

Goscelin’s account relates how Werburgh had chosen Hanbury as her resting-place. In fact, she died at Threekingham, where the community locked the body away until it was miraculously delivered to the people of Hanbury in accordance with the wishes of the saint. When the monks came to collect it the watchmen were overcome by sleep and the locks and bars they had installed fell to the ground. Thereafter the saint was taken to Hanbury, where she performed many miracles and where nine years later her incorrupt body was enshrined by King Ceolred. The prologue alludes briefly to Werburgh’s resting place at Chester but the remainder of the text contains no reference to its translation. Furthermore, it refers to the disintegration of the saint’s hitherto incorrupt body, which at the moment of removal from Hanbury “fell to dust” to prevent it falling into the invaders’ impious hands. In fact, the community with the greatest reason to remember Werburgh around 1100 was Ely, the burial place of her mother Eormenhild, her grandmother Seaxburh, and her great aunts Aethelthryth and Wihtburh. Moreover, Goscelin expressly commends the tomb of Eormenhild at Ely as the place at which Werburgh should be venerated.[8]

Ely

The life of the Ely community was disrupted by Danish attacks in the late 9th century. The cult of the foundress Aethelthryth undoubtedly continued however, and the restoration of the community by St Aethelwold in 970 inaugurated a revival of interest in the cult of that saint and her relatives – Werburgh’s forbears. In the early 12th century there was a renewed interest in the sanctity of the Ely princesses, promoted by the new abbot, Richard of Clare after his return from Rome in the company of Archbishop Anselm (later Archbishop of Canterbury). In 1106 the saints’ bodies were removed from the resting-places allotted to them by Aethelwold and translated to new monuments in Abbot Richard’s new monastic choir. The discovery of Werburgh’s uncorrupted body at Hanbury gave fresh impetus to the devotion. It was at this point that Professor Love thinks Goscelin’s Vita was composed. Thereafter we find all the Ely princesses given prominence in the Ely calendar, which commemorates both the depositions and translations of those actually enshrined. Werburgh was commemorated on the day of her death but without any mention of her translation to Chester.[9]

Chester

There is a growing amount of evidence that Chester was a centre of Romano-British Christianity and the area remained a place of significance in British Christianity. It included the famous monastery of Bangor-is-y-Coed just a few miles distant the destruction of which is recorded by Bede after monks were sent to assist at the battle of Chester in 616.[10]; The Chester monk Ranulf Higden, relates that because of the Danish raids on Mercia the Hanbury community fled taking the shrine containing the holy relics and sought refuge in Chester.[11] Higden claimed that from the time of King Aethelstan there existed a minster of canons to serve the saint. This account has been doubted, partly because the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle described Chester itself as a deserted place in the entry for the year 893.[12] Saint Werburgh’s relics were certainly enshrined at Chester by 958, when King Edgar made a grant of lands to the saint’s familia (religious community) there.[13] Florence of Worcester adds that Leofric, earl of Mercia (d.1057), enriched the house with valuable ornaments. By the time of Domesday Chester was an ancient royal and ecclesiastical centre, the home of two important minsters and the shrine of Saint Werburgh.

Although Higden’s account is possible, a more detailed account of the translation of the relics to Chester is given by Henry Bradshaw d.1513, the latest of the chroniclers. Writing in verse shortly before the Reformation and the advent of the printing press Bradshaw’s Holy Lyfe and History of Saynt Werburge, very frutefull for all Christen people to rede.” had the advantage of being printed within a decade of his death by Pynson.[14] Bradshaw describes, “the gostly devocion of Saynt Werburge, and vertueous governans of her places.” and her character as, “piteous and merciful and full of charity to the poor people in their necessity.” Various miracles are described and, when at her monastery at Triccingham (Threekingham, Lincs.), she felt her end approaching, she gave her last exhortation: to live in temperance, obedience, and love; recited the Creed’ received the Holy Gifts; and, “The third day of February, (c700) ye may be sure, expired from this life, caduce (fleeting) and transitory to eternal blyss, coronate with victory.” Buried first at Threekingham and moved to Hanbury where the incorrupt relics were venerated Bradshaw goes on to describe, “The relique, the shryne full memorative, was brought to Chestre for our consolacion, reverently received set with devocion in the mouther Churche of Saint Peter and Paule.” A full description is given of the solemn reception of the shrine, and also of the gifts of the faithful, “The people with devocion and mynde fervent gave divers enormentes unto this place, some gave a cope, and some a vestemente, some other a chalice, and some a corporace, some crosses of golde, some books, some belles, the poor folk gave surges (woollen fabric), torches and towelles.” Bradshaw states that the rulers of Mercia, Aethelred and his wife King Alfred’s daughter Aethelflaed set up the shrine in the mother church of Chester which they enlarged and dedicated to the saint. Bradshaw’s main source, the “third passionary” now lost, contained the Lives of Saint Werburgh and the Ely abbesses and he added accounts of a sequence of miracles that occurred after the translation. Since the sequence of miracles ends in 1180, it is thought that the document was composed shortly after this date. There is also some information in Lucian’s Chester service book De Laude Cestriae which dates from that time.[15]

Aethelred, Earl of Mercia and Aethelflaed had been in Shrewsbury in 901 when they enriched the Church of St Milburga at Much Wenlock with gifts of land and a valuable golden chalice.[16] About this time Aethelred began to suffer from some debilitating illness and Aethelflaed herself became the ruling force in Mercia.[17] Evidently as part of the defence of Wirral against Norse from Ireland she refortified Chester in 907 after repelling the invaders and, just two years later in 909, she was responsible for the translation of the relics of Saint Oswald from Bardney to a new foundation in their fortified capital of Gloucester.[18] When Aethelred died in 911 he was buried beside the shrine in Saint Oswald’s Monastery, Gloucester. Aethelflaed, the most formidable royal female since Boudica, continued to rule Mercia alone with the appellation Myrcna hlaedige (Lady of the Mercians). After leading a successful expedition into Wales to avenge the murder of an abbot, Aethelflaed recognised an opportunity to defeat the Vikings and negotiate for a lasting peace so she and her brother, Edward the Elder, launched a concerted campaign against the Danes in 917. Invasions by three Viking armies failed as Aethelflaed’s Mercian forces captured Derby and the five main towns of Danish Mercia. This marked a tremendous victory for Aethelflaed who in 918 gained possession of Leicester without opposition and a few months later the great Viking stronghold of York also submitted to her after she formed an alliance with Welsh kings, the Kings of Strathclyde and Bernicia and the Scottish King Constantine. It is thought that the relics of Saint Werburgh were translated from Hanbury to Chester at some point in this period probably after the conquest of Staffordshire in 913.[19]

Like Oswald, Milburga and Alchmund, Werburgh’s royal connections no doubt resonated with Aethelflaeda. Evidently devotion to Saint Oswald was well established by the time of Bradshaw who tells us that it was introduced into Chester by Aethelflaedea the patroness of her new royal burh. Numerous entries in the cartulary of Chester Abbey refer to the parish as either Saint Oswald’s or Saint Werburgh’s:[20] an altar to Saint Oswald exists in Chester Cathedral to this day. The foundation of Saint Werburgh was supported by Kings Aethelstan and Edmund, both of whom are said to have founded a house of canons in her honour. That she continued to be venerated there is clear from King Edgar’s grant of 958 and the enrichment of her church with precious ornaments by Earl Leofric of Mercia (d. 1057).

Bradshaw tells us that the monks took the shrine of Saint Werburgh to the walls of the city when it was besieged by Gruffudd ap Llywelyn king of Gwynedd. The shrine was damaged in the attack and as a result the Welsh king and his host were smitten with blindness and retreated.[21]

Hugh “Lupus” d’Avranches, 1st Earl of Chester refounded the minster as a Benedictine abbey in the late 1080s and early 1090s. Hugh’s closest friend among the higher clergy, the prelate chosen to dedicate his new foundation, was Anselm, abbot of Bec, soon to become archbishop of Canterbury. The first abbot of Chester, Richard (1092–1116), was a monk of Bec and according to Ranulf Higden had been Anselm’s chaplain.[22] William of Malmesbury in the 12th century provides us with contemporary witness of miracles wrought at the shrine. Evidently it was a portable shrine because it was carried about in processions, and in times of danger and emergency it was “set on the towne walles” to save Chester from the attacks of the Welsh; and again, “The devout Chanons sette the holy Shryne against their enemies at the sayd Northgate when innumerable barbarike nations puposd to distroye and spoyle the cite.” Bradshaw tells us “howe in 1180 a great fire, like to destroye all Chestre, by miracle ceased when the holy shrine was borne about the town by the monkes.” He goes on to tell how the fire quickly consumed a great part of the town including the minster of Saint Michael at the Roman south gate but the monks came from the abbey bearing the shrine of Saint Werburgh and chanting litanies. The blaze was thus extinguished. The anniversary of her death on Feb. 3rd was commemorated at Ely and, most notably in Shrewsbury’s episcopal minster of Saint Chad, the twelfth-century calendar also included the translation feast on June 20th. The magnificent shrine built in medieval times was destroyed at the Reformation when parts of it were recycled into an elaborate Bishop’s throne. In 1876 its scattered portions were re-assembled by one of the cathedral’s restorers, Sir A. W. Blomfield. Today the reconstructed shrine stands in the Lady Chapel where it remains a place of pilgrimage.[23]

Shrewsbury

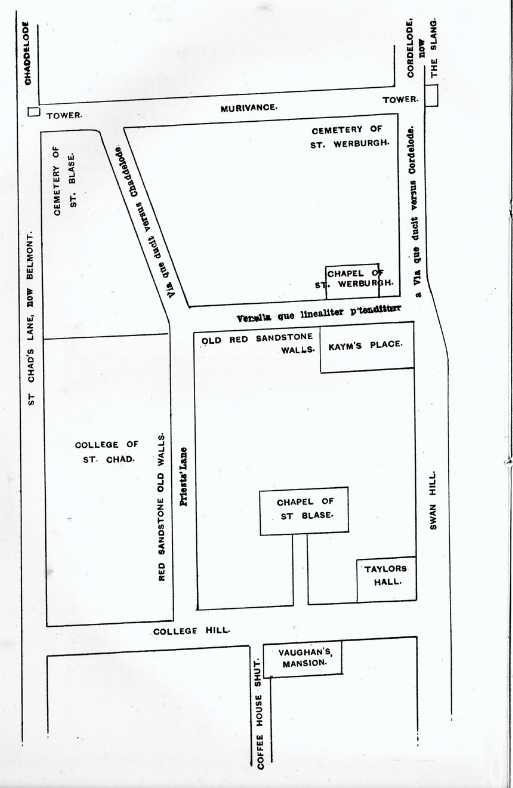

In 901, when it is first referred to in written sources, Shrewsbury was already of very considerable importance. Evidently it was a royal centre at which Aethelred, the Alfredian governor (patricius) of Mercia, and his wife Aethelflaed, daughter of Alfred the Great, held a witan. By then it must have been a fortified burh in common with the other shire towns of England. The mint which was operating at Shrewsbury by the later part of Edward the Elder’s reign (899-924) was a characteristic feature of its status.[24] By Domesday it was a large and valuable royal borough with 252 houses and six important churches. Saint Alchmund’s and Saint Mary’s had been founded in the tenth century by Aethelflaed and King Edgar respectively while Saint Chad’s was the property of the see of Lichfield. The charter issued in 901 was effectively a deed of gift to Saint Milburga’s Abbey at Much Wenlock of a large amount of property and “a gold chalice weighing thirty mancuses for the love of God and for the honour of the venerable virgin Mildburg the abbess”. Devotion to Saint Milburga had survived the Danish invasions without interruption.[25] Elsewhere Aethelflaed was responsible for the removal of numerous relics for safety. Not only were the relics of Saint Oswald rescued from Bardney and enshrined in a new minster at Gloucester closely linked with the royal residence at Kingsholme and Saint Werburgh enshrined in Chester but also at Stafford Saint Bertelin was enshrined in an ancient royal minster.[26] Aethelflaed seems to have followed a deliberate policy of promoting devotion to Mercian saints with royal connections in her fortresses. The only record of the observance of both the days of the death and translation of Saint Werburgh at Saint Chad’s has already been noted. This observance may be in some way connected to a chapel dedicated to Saint Werburgh. There are several early 13th century references to this chapel and to a street named after the saint (in vico Sancte Werburge). The earliest mention of it is in the Haughmond Cartulary which suggests that it was already well established then.[27] A later deed also mentions the chapel of St Werburgh the Virgin, and a cemetery belonging to it is referred to in 1305 and 1308.[28] Significantly they were both in the ancient parish and close to the old church of Saint Chad. Red sandstone walls and foundations thought to be from this chapel were recorded in Swan Hill Court in 1888 and 1897.[29] Blakeway in his History of Shrewsbury identifies the present Belmont, which runs alongside Old Saint Chad’s as the former Saint Werburgh Street.[30] Hobbs in Streets of Shrewsbury convincingly identifies the site of the chapel as the court yard of 9 Swan Hill, just a few yards from St Chad’s where the two feasts mentioned were observed.[31]

The connection between no less than three historic church foundations in Shrewsbury is of course Aethelflaed. The church at Sutton, south of the river as its name implies, was held by the monastery of Saint Milburga of Wenlock a foundation known to have been supported by Aethelflaed. The foundations of a large Saxon church with a rounded apse have been discovered here in a recent archaeological investigation.[32] Then we have Saint Alchmund’s which she founded probably in association with the recovery of his relics from Derby and lastly we have an ancient chapel dedicated Saint Werburgh.[33] Religious foundations dedicated to Milburga, Alchmund and Werburgh, all Mercian saints with royal connections like Oswald, were either created or enriched by Aethelflaed who was evidently keen to promote veneration of them in fortified burghs in her kingdom.

Today these pre-Schism saints are venerated in the Orthodox Church and in particular here in Shrewsbury in the Church that was founded by Saint Milburga’s Monastery. Here their part of Christian heritage is measured with a different gauge than the conclusions and opinions of historians. Maximos the Confessor, roughly a contemporary of Saint Werburgh in the seventh century, taught that the one and only Hagios (saint) is God Himself and that people become holy ie ‘sainted’ by participation in the holiness of God. Saints, he says, are people who have achieved unity with God through the Holy Spirit (Theosis)[34]. Accounts of their holy lives come to us now, as the poet Thomas Traherne says as “News from a foreign country, as if my treasures and my joys lay there.” The truth and beauty is not in the accounts of the lives of the saints, however much or little they are valued by historians, it comes through them. The saints are not regarded as super-human beings above and beyond us but people like ourselves who in some way reflect the holiness of God Himself. Their stories, like the Icons of them do not, nor ever were intended to, present a factual historical or photographic likeness. They are deliberately written or painted in a stylized way that is intended to convey a sense of their holiness.

Hearing the story of a saint like Werburgh or contemplating an Icon of her or any saint we enter personally into the mystery and the Kingdom of God becomes potent like the scent of a flower we have not found or the echo of a tune we have not heard. They connect us to the Communion of Saints and the fullest encounter with the Kingdom in the Divine Liturgy which begins with the words, “Blessed is the Kingdom of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit.”

Christopher Jobson January 2022

Doxastikon for the Feast of our Venerable Mother Werburgh, Abbess of Mercia

Though you were the fruit of many royal lines, O Werburgh, royal virgin, yet you did not boast in your lineage, nor did earthly allurements distract your soul from the contemplation of the Lord of lords, Whom from childhood you loved love with all your heart. Then, mindful of the words of David the King, that the daughters of kings forget their own people and their fathers’ house, with the virgins in the train of the Queen of heaven you brought yourself into His holy temple in gladness and rejoicing, arrayed in all the virtues, as in gold-fringed garments of varied colours. Wherefore, praising your humility, all Christians commemorate your name forever, O glorious one. (from the service for the commemoration of our Venerable Mother Werbugh composed by Reader Isaac Lambertson)

[1]Also spelled Wærburh, Werburh or Werburga.

[2]Hebrews, 12,1

[3]A. Thacker, The Land of the English, chap. 22, p.443

[4] A. Thacker, The Land of the English, chap. 22, p.443

[5] Rosalind Love, ed. and trans., Goscelin of Saint Bertin, pp. xv-xvii

[6] A. Thacker op. cit.

[7] D.W.Rollason, “Lists of Saints’ Resting-Places in Anglo-Saxon England”

[8] Thacker op.cit. chap. 22, pp. 443-446

[9] Thacker ibid

[10] Bede, Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum

[11] Ranuf Higden, Polychronicon, Rolls Series vol.vi. pp.126-179 (I am grateful to the Hon. Librarian of Chester Cathedral for access to this important text.)

[12] Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, trans. Garmonsway, p.88

[13] Victoria County History (hereafter VCH), Chester

[14] Chester Arch. Soc. Journal (hereafter CAS) 1903 quotes Bradshaw: Bradshaw’s text is on www.archive.org

[15] VCH Salop. IV2 pp.23-23

[16] The primary account of Aethelflaed is in a version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle known as the Mercian Register; although it is now lost, elements were incorporated into several surviving versions of the Chronicle. The Register covers the years 902 to 924: Trans.Shrop.Arch.Soc. IV,1,pp.4-6 for text of the charter.

[17] T.Clarkson, Aethelflaed, The Lady of the Mercians 2018

[18] A.Thacker, Chester and Gloucester, Midland History, p.207

[19] A. Thacker op cit

[20] A. Thacker op cit

[21] Cart, Chester Abbey, cf. Thacker p.457

[22] A. Thacker op cit

[23] CAS, 1915

[24] TSAS, op cit : S. Bassett, Anglo-Saxon Shrewsbury etc., Midland History

[25] VCH, Shropshire

[26] A. Thacker, Kings, Saints, and Monasteries in Pre-Viking Mercia, Midland History 10

[27] Haughmond Cart. ed Rees, 1076-1080

[28] VCH, Shropshire iv2

[29] TSAS, 11, p.92-3 diagram & trans. of deed 1305

[30] Owen &Blakeway, Shrewsbury II.475

[31] J.L.Hobbs, Shrewsbury Street Names, 101-2

[32] Baskerville Archaeological Services, Report Jan.2018

[33] VCH IV2

[34] Maximus the Confessor, On the Ecclesiastical Mystagogy, trans. Jonathan J. Armstrong: