- 23 February

The conversion of Mercia

The story of Saint Milburga begins with the conversion of the Kingdom of Mercia to Christianity. According to Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of England the pagan king Penda, who had murdered Saint Oswald at Maserfield (Oswestry), was converted by his brother in law, Alchfrid, a grandson of Saint Oswald, in 655. Dinma, one of the four priests who were then sent to preach and baptise, became the first bishop of Mercia. Later that year Penda was killed and was succeeded by Oswy whose three-year reign was terminated by a rebellion, which resulted in the restoration of Penda’s son, Wulfhere, as king. He was described by Florence of Worcester as “the first Christian king of all Mercia and he was zealous in putting down idolatry”. It was at his request that Saint Chad was brought from his retreat at Lastingham accompanied by a holy monk called Owini (Owen) to establish the episcopal see at Lyccidfelth (Lichfield).

Saint Milburga’s father, Merewald, another son of Penda who ruled a subkingdom called Hecani (south Shropshire and Herefordshire), had been converted from paganism in the year 660 by a Northumbrian priest named Eadfrith and had married as his second wife a Christian princess from Kent named Ermenburga (or Domneva). Later she returned to Kent and there founded the convent at Minster in the Isle of Thanet becoming the first abbess while Merewald was enthusiastically spreading the Christian Gospel in his kingdom. Thus it was that their eldest child, Milburga, was born a Christian princess related to the royal houses of Kent and Mercia. Like her sisters Mildthryth (Mildred) and Mildgeth (both later honoured as saints) she was educated at the nunnery at Chelles, which brought her into contact with the organisation of double monasteries of men and women.

Founding of the Monastery at Wenlock

Milburga was resolved to found just such a monastery in her father’s kingdom with the help of Saint Botulf, Abbot of Icheanog (possibly Iken in Suffolk). He set up a monastery at Wimnicas (later Wenlock – white monastery) under an experienced Frankish abbess called Liobsynde. In her testament, written shortly before her death in 727, St. Milburga recorded the arrangement by which she obtained Wimnicas from Saint Botulf’s monastery and the Abbess Liobsynde “…an estate of 60 hides at a place called Hampton…” She then proceeds to give the text of the charter written for her by Abbot Edelheg in which the Wenlock estate is stated to be 97 hides and the tutelage (pastoral oversight) is retained by St. Botulf’s.

Disciple of Saint Owen

Archaeological investigation has done much to unearth details of St. Milburga’s monastery. The most recent findings are that the walls of the earliest church on the site of the monastery, until now thought to be Saxon, are in fact remains of a complex of abandoned Roman buildings that were reoccupied in the seventh century. According to tradition St. Milburga was attracted to Wimnicas by the saintly life of St. Owen who was living in a hermitage there. It seems likely that this was the holy monk Oweni who had accompanied St. Chad to Lichfield. Such a hermitage would have been in character with Celtic monasticism as received from Egypt via Gaul and practised in the sixth and seventh centuries. Each monk normally lived apart in his own cell, preserving the hermit’s isolation within the community but at the same time owing strict obedience to the abbot or abbess. This pattern of community life is still to be found in the Orthodox Church at such places as Mount Athos in Greece. It is notable that there exist to this day two holy wells at Much Wenlock, one dedicated to St. Milburga and the other, quite near to the parish church, to St. Owen.

A double monastery at Wenlock

It has been suggested that the present parish church of Much Wenlock marks the site of St. Milburga’s original church, which was also dedicated to the Holy Trinity and possibly St. Owen’s hermitage. This is given some support by a manuscript recently discovered in Lincoln Cathedral Library, which contains an account of a visit in 1101 by Odo, Cardinal Bishop of Ostia, to investigate the claims of miracles resulting from the newly discovered relics of Saint Milburga. This document makes it quite clear that St. Milburga had been buried in a pre-conquest church “about a stone’s throw away from the minster” which suggests the present parish church. Recent archaeological investigation prompted by this information has attempted to identify fabric contemporary with St. Milburga in the south aisle and the Lady Chapel. St. Boniface in one of his letters refers to the vision of a monk who, he says, was “in the convent of the Abbess Milburga”. This is now taken as confirmation that the original foundation was not only a nunnery but also a double monastery with two churches, one each for men and women and ruled by an abbess: it seems natural that a newly founded monastery in a recently converted kingdom with no local precedents to follow should adopt the pattern of the motherhouse. In this case, as we have seen, it was Icheanog, which had been founded by St. Botulf who, like St. Milburga, had been educated in the double monastery at Chelles in Gaul.

Wenlock – a vigorous centre of Christianity

The importance of Wimnicas and Saint Milburga can be seen from the extent of the territory donated to the monastery during her lifetime, much of which was still held at the time of the Norman Conquest. For instance several charters record that between 674 and 704 her half brothers Merchelm and Milfrid granted “63 manetes” in various places, some around Clee Hill, at Stoke St. Milborough, Clee Stanton, along the River Corve and also Sutton (where the medieval church building may have been built on earlier foundations), Easthope Patton, Burton, Shipton, Chelmarsh, Eardington, Deuxhill and Madeley. There were also properties which were later lost in Wales, Worcestershire and Herefordshire. It is also worth noting that Wenlock is the only pre-conquest monastic foundation in Shropshire and it is in one of its charters dated 901 that, In civitate Scrobbensis, the earliest reference to the name that developed into Shrewsbury, is found.

The royal saint-abbess, Milburga, must have been for Mercia and Wimnicas what Saint Hilda was for Northumbria and Whitby and Saint Brigid for Ireland and Kildare. As both a princess of considerable importance and abbess of what was probably the most vigorous centre of Christianity in her father’s kingdom, St. Milburga must have been a formative influence at a critical period in the history of Christianity in the British Isles. She, like her father, had received Christianity in its Celtic form from Iona via Northumbria and her venture seems to have flourished just as the disciplined hierarchy of Rome was demanding conformity making the Roman tonsure and the Roman Easter the symbols of submission in the century following the Council of Whitby in 664. Her consecration as abbess had been among the first undertakings of the aged St. Theodore, himself a monk of the Eastern Church, following his appointment as Archbishop of Canterbury in 667.

St. Milburga’s achievement must be seen in the context of the Celtic monastic movement that began in Wales in the 530’s that spread first to Ireland then, by way of Iona, to the English and thereafter sent its missionaries to Europe. It was this movement that resulted in the conversion of the peoples beyond the Rhine and Danube frontiers of Rome and founded most of the early monasteries of Europe north of the Alps. St. Boniface, whose letter provides evidence of the double monastery at Wenlock, became Archbishop of Mainz and apostle of Germany and was finally martyred while on a mission to Holland in 754 AD.

Milburga the Wonderworker

Of the numerous miracles recorded in connection with Saint Milburga several relate to her lifetime and others result from the discovery of her relics. The first and most famous concerns an occasion when a Welsh prince who was overwhelmed by her beauty was pursuing her. The saint was saved from his amorous advances by a sudden rising of the waters of the river Corve near the spot where St. Peter’s Church was eventually built at Stanton Lacy. At Stoke St.

Milborough, where she was thrown from her mount, it is said that Saint Milburga miraculously obtained water to bathe her wounds from a spring that issued forth from a rock struck by her horse at her bidding. The church and a holy well there are both dedicated to her while at Stanton Lacy much of the Saxon church fabric still survives. On another occasion Saint Milburga restored a dead child to life again and the suspension of her veil in the air was taken to be a miraculous sign. She is particularly associated with the miraculous protection and growth of crops and she is usually portrayed with geese, which are said to have obeyed her orders.

The discovery of her relics in 1101 was attended by several other miracles. William of Malmsbury records the sweet odour that pervaded the church when the relics were exhumed.

Cases of leprosy and blindness were cured and in one dramatic incident a woman’s suffering was relieved when she vomited a “monstrous worm”.

The double monastery seems to have thrived for just over two centuries and probably perished at the hands of Danish invaders. The Church of Holy Trinity was left in ruins and the site of the saint’s burial eventually lost. The community was not entirely destroyed however, for the charter of 901 shows that a community of nuns was then being served by a college of secular clerks who may have led some form of community life under a male superior but were not following any particular rule. In this same charter Aethelred, Earl of Mercia and Aethelflaeda, ‘Lady of the Mercians’ (daughter of King Alfred) restored some property at Easthope and Patton and bestowed a further three hides in Barrow and “a gold chalice weighing thirty mancuses….for the love of God and for the honour of the venerable virgin Mildburg the abbess”. This revival of an ancient foundation, under royal auspices was, according to recent research, like many others, linked with royal administrative centres. In this context St. Milburga’s property at Sutton, detached from Wenlock and isolated at a northerly point among the ancient parishes of Shrewsbury, is significant. It would have been in character for Aethelflaeda, who is known to have rescued the relics of numerous other royal saints, to have rescued those of the royal saint-abbess Milburga and brought them to Sutton, which was within the area controlled by the administrative centre of Shrewsbury. When the Danish threat was over the relics may well have been returned, like those of Saint Alkmund which were returned to Derby from Shrewsbury, soon after the Norman Conquest.

Following the Norman Conquest Earl Roger Montgomery, himself a benefactor of the largest and most famous monastery in the west at Cluny, established Wenlock as a Cluniac priory under the direction of the priory of La Charite-sur-Loire. In accordance with the policy of this expanding network of houses following the Benedictine rule a grand new priory church one hundred feet in length and thirty feet wide with three apses was built on the site of the ancient monastery church of Saint Milburga’s double monastery. Following their arrival in 1079 the new monks, evidently disappointed at finding no relics of the patron saint, began to speculate on the possible resting place of her bones. A manuscript was discovered in the ruins of the church written in the “English tongue” from which they learnt that the saint was buried before the altar. Permission was sought and obtained from the Archbishop of Canterbury to excavate the floor of the old church. This proved to be unnecessary for by a remarkable coincidence on the eve of Saint John the Baptist’s Day the grave was accidentally discovered by some children who were playing there while the monks were singing the Divine Office in the monastery church.

With the precious relics of its illustrious foundress carefully enshrined the prosperity of the medieval monastery was ensured by the revenue of the growing number of pilgrims and the donations of money, property and land. The monastery church of Wenlock was rebuilt on a magnificent scale when Humbert was Prior (1221 – 1261) to accommodate the growing numbers of monks and pilgrims and the elaborate ceremonial for which the Cluniacs were famous. The church at Sutton was probably rebuilt at this time giving the monastery a presence on the edge of the county town. It was the prosperity of Wenlock that led the Abbot of Shrewsbury to procure the relics of Saint Winifride and to establish a place of pilgrimage there rather than provide a hostelry for pilgrims on their way to Wenlock.

The fortunes of Wenlock Abbey are reflected in the extensive rebuilding and improvements made to the monastic buildings and the Lady Chapel in the years following the rebuilding of the Abbey Church and, in 1501, the magnificent shrine built at the order of Henry VII. The end came with the Reformation in January 1540 when Wenlock Priory was given to Cardinal Wolsey’s physician who sold it to Thomas Lawley. The prior’s house and the infirmary were converted into a private house, which is still in use, but the rest was heavily plundered and reduced to ruins. The bells were melted down to make cannon for Henry VIII’s battleships and the relics of Saint Milburga were burnt in the market place.

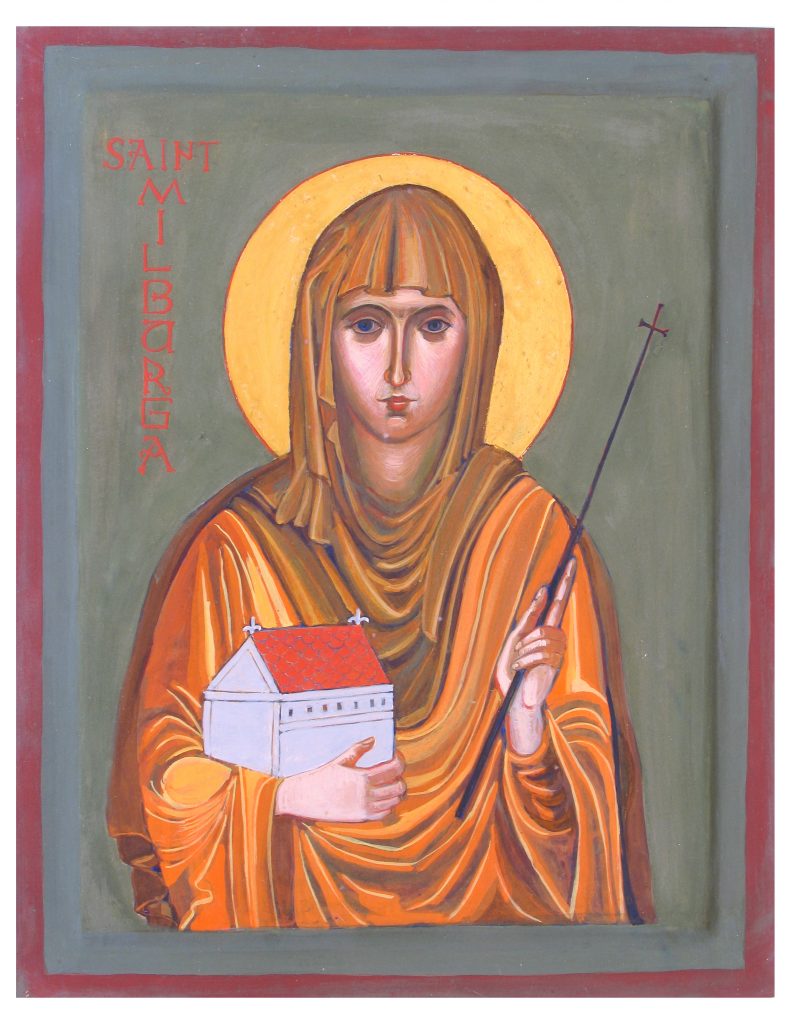

In recent times the Orthodox Community of the Holy Fathers of Nicaea has carefully restored the derelict ruin of the ancient church on Saint Milberga’s estate at Sutton and now the name of Saint Milburga is honoured among the saints in the Divine Liturgy with the words of the troparion:

O Holy Princess and Abbess Milburga You established a monastery to show forth Christ Your burial place was revealed by your fragrant relics You healed the sick and raised the dead Pray for us that our souls may be saved.

-oOo-

Christopher Jobson

Saint Milburga’s Day 2012

Saint Milburga and Winifrid Pilgrimage route