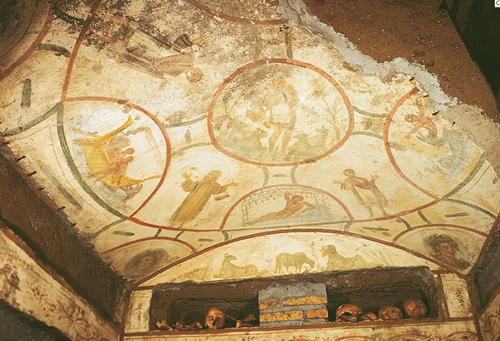

I want to write about tombs, sheep and sea monsters… And yes, I know it sounds like the beginning of a bad joke. But in actuality, these things are related quite profoundly to each other. I want to draw your attention to an impressive and enigmatic painting. It adorns a ceiling within the Catacombs of Saints Marcellinus and Peter, and roughly dates to the beginning of the 4th century.

The art above each wall is circumscribed, forming part of a larger cruciform shape which centres on the image of a shepherd. Each extremity of the cross depicts a scene from the life of the prophet Jonah. On the left, we see Jonah being tossed overboard; on the right, we see Jonah being swallowed by the sea monster; at the bottom, we see Jonah being covered by a newly created plant.

The central image, which depicts a shepherd amidst his flock with a sheep on his shoulders, also occupies the highest point of the arched ceiling. So, artistically and architecturally, its significance in relation to the other images cannot be overlooked. Yet, with this in mind, a few questions arise. What relation do the images have to one another? And also, why are such images appropriate for a Christian burial setting. Both answers are to be found in the hope provided by Christ.

The Shepherd

In an attempt to unearth the wealth of meaning contained within the central motif, I want to draw attention to how the early Christians initiated people into the Church. Those wishing to join the Church would undergo a process of instruction, or ‘Catechism’, which usually occurred during the Lenten period, and culminated with the catechumen being baptised on the eve of Pascha. After being washed clean, the baptizand was given a white robe and a candle. They had now been ‘illumined’, and so journeyed east towards the altar to receive Holy Communion. As part of their instruction, the catechumens had to learn the Our Father by heart. Following the Council of Nicaea (325), a recitation of the Nicene Creed was also required. Though prior to the council, local creeds were used instead in the form of interrogations. The bishop would ask if certain principles of faith were held, and the baptizand would respond accordingly. Interestingly, it seems like another text was learned by the catechumen specifically for their initiation into the Body of Christ on the night before Pascha.

In On the Mysteries, St. Ambrose of Milan (d.397) describes the newly illumined as, “Having put out the stain of the old error, his ‘youth renewed like the eagle’s,’ he hastens towards the heavenly banquet. He arrives and, seeing the altar prepared, he cries out: ‘You have prepared a table before me’”. As the baptizand approaches the altar to receive the Eucharist, it is Psalm 22 (23) that is uttered. Within this Davidic hymn, one can see both a summation of the sacraments of initiation, and the structure of our life in Christ. Psalm 22 (23) reads as follows:

1 The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want.

2 He maketh me to lie down in green pastures: he leadeth me beside the still waters.

3 He restoreth my soul: he leadeth me in the paths of righteousness for his name’s sake.

4 Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for thou art with me; thy rod and thy staff they comfort me.

5 Thou preparest a table before me in the presence of mine enemies: thou anointest my head with oil; my cup runneth over.

6 Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life: and I will dwell in the house of the Lord for ever.

Throughout the Fathers, the ‘green pastures’ have been seen as referring to catechism, Scripture and the doctrine of the Church. Clearly, the ‘pastures’ embody that which instruct and guide us. Sheep consume luscious grass, and by consuming it, they draw it into themselves and are changed by the process. Similarly, the spiritual food of the Church, according to St. Cyril of Alexandria (d.444), ‘nourishes the hearts of believers and gives them spiritual strength’. The intake of ‘green pastures’ orientates us towards God, and thus towards our next step in the process of initiation: baptism. We are led ‘beside the still waters’, and at the waters we journey ‘through the valley of the shadow of death’. As St. Paul explains in Romans 6:3-4, those who have been baptised into Christ have died with Christ. We have participated in His death, and it is for this reason that, according to St. Cyril, ‘Baptism is called a shadow and an image of death, which is not to be feared.’ For St. Cyril, the ‘green pastures’ also take on an eschatological dimension. Our entire sacramental life, which begins at baptism, aims to bring us to the place of green pasture. Hence, he writes, ‘The place of pasture is the Paradise from which we fell, to which Christ leads us and establishes us by the water of rest, that is to say, by Baptism’.

The gift of the Holy Spirit to the believer is also conveyed by the Psalm at two points. The first is in verse 4: ‘thy rod and thy staff they comfort me.’ In the Septuagint, (the Greek translation of the Old Testament), the word often translated as ‘comfort’ or ‘guide’ is ‘paraklesis’, which bears a close connection to ‘Paraclete’ (a term used by St. John the Evangelist to speak of the Holy Spirit). Thus, St. Gregory of Nyssa (d.c.395) writes, ‘He guides him by the staff of the Spirit: for indeed the Paraclete (he who guides) is the Spirit.’ The second, and more obvious section associated with the outpouring of the Spirit is found in verse 5: ‘thou anointest my head with oil’. St. Cyril of Jerusalem (d.386) explicitly links this verse with the Mystery of Chrismation in his Lectures on the Christian Sacraments. He writes, ‘With oil he anointed your head upon the forehead by the seal, which you have from God, that by the impression of a seal he might make you holy to God.’ Although, ‘your body was anointed with visible Myron [the oil used in Chrismation]’, ‘your soul was sanctified by the Holy and invisible Spirit’.

In verse 5, we also read, ‘Thou preparest a table before me in the presence of mine enemies’, and ‘my cup runneth over’. Again, the Fathers are in harmony as to what this prefigures. Recall the quote from St. Ambrose which describes the newly illumined approaching the altar to receive the Eucharist, crying out, ‘You have prepared a table before me’. As St. Cyril of Jerusalem notes, ‘what else can he [David] intend but the mystical and spiritual table, which God made for us against, that is, in opposition to, the evil demons?’ More directly, St. Cyril of Alexandria writes, ‘The sacramental table is the flesh of the Lord, which fortifies us against the passions and the demons.’

To see the Eucharistic Mystery within ‘my cup runneth over’, we must look to the Septuagint translation, which reads, ‘inebriating chalice’. The association between this part of Psalm 22 (23) and the Eucharist occurs extremely early in the history of the Church; more specifically, in the work of St. Cyprian of Carthage (d.258). He writes, ‘the inebriation that comes from the chalice of the Lord is not like that given by profane wine. The chalice of the Lord inebriates in such a way that it leaves us our reason’. He writes, ‘as common wine releases the spirit, sets the soul free and banishes all sorrow, so the use of saving Blood and of the chalice of the Lord banishes the memory of the old man, bestows the joy of the divine goodness in the sad and gloomy heart which before was weighed down by the load of sin.’ It is for this reason that St. Gregory of Nyssa refers to the effects of the chalice upon us as a ‘sober inebriation’.

I now return to verse 1, ‘The LORD is my shepherd; I shall not want’. The Shepherd of this Psalm is Christ. In the Gospel of John, Christ explicitly refers to Himself as ‘the good shepherd’ Who ‘gives His life for the sheep’ (John 10:14). In John 10:7, Jesus self-identifies as ‘the door of the sheep’, remarking in verse 9 that, ‘If anyone enters by Me, he will be saved, and will go in and out and find pasture’. As we have seen, Psalm 22 (23) encapsulates our initiation into (and participation in) the sacramental life of the Church; a life which we can only access through Christ, ‘the good shepherd’ and ‘door of the sheep’. Perhaps it is for this reason that early baptistries are frequently adorned with depictions of the Good Shepherd. For example, the baptistry of the Dura-Europus church contains the following painting from the early 3rd century:

Here, we can see the shepherd watching over his flock. An allusion to Luke 15:5 can also be discerned, where Christ suggests that upon finding a lost sheep, a good shepherd ‘joyfully puts it on his shoulders’. The Baptistry of San Giovanni in Fonte, Naples, contains a clearer depiction of the scene. It dates back to sometime within the 4th century:

And even though it is not a pictorial depiction, the arch above the font in the Baptistry of Neon in Ravenna (which dates to the late 4th/early 5th century) invokes the idea of the Good Shepherd via a Latin inscription of the first two verses from Psalm 22 (23):

Apart from baptistries, the image of the Good Shepherd features most prominently in Christian tombs. For example, the Catacombs of Domitilla in Rome contain the following painting which roughly dates to the middle of the 3rd century:

And the Catacombs of Priscilla in Rome contain a fresco from c.225:

Thus, it seems like our original image fits snuggly into a widespread tradition of its time. With all this in mind, we can now attempt to answer why depictions of the Good Shepherd are appropriate for Christian burial sites. And it is related to why such depictions are appropriate in baptistries. The Good Shepherd is ‘the door of the sheep’, and as such, exemplifies the stepping over from one state to another. Recall that Psalm 22 (23) was learned for initiation. It played a part in the initial promise given to believers as they entered the Church’s liturgical life. Through baptism, we exchange sin and death for forgiveness and Life. We are ‘born again’, and begin a new, sacramental life; a life that, when lived faithfully, propels us ever forward towards Christ. And by integrating ourselves fully into the liturgical life of the Church, we die in the hope that we may enter the ‘green pastures’. The Good Shepherd marks the boundaries of our life in Christ. For the early Christians, it is an image that accompanies them through their transition from death to life at baptism. And so, it seems only fitting that they would want to be buried under this image at the next point of transition, as they await their resurrection to Life (John 5:9).

These ideas can also be seen in the Church today. During the Trisagion Prayers for the Dead, the priest implores, ‘O God of spirits, and of all flesh, who has trampled down death, crushed the power of the Devil, and granted life to your world, do you yourself O Lord, give rest to the soul of your servant… who has fallen asleep, in a place of light, a place of green pasture, a place of repose, where there is no grief, sorrow or mourning.’

Jonah

Like the Good Shepherd, images of Jonah dominate early Christian graves. Yet, unlike the Good Shepherd, the suitability of the life of Jonah in a burial setting is much more straightforward to see. In the story of Jonah, a sea monster swallows him whole, and drags him into the abyss where he remains for three days. The Fathers saw this as a type of Christ’s resurrection. Christ Himself even makes this connection explicitly in Matthew 12:38-45, where we read:

38 Then some of the scribes and Pharisees answered, saying, “Teacher, we want to see a sign from You.”

39 But He answered and said to them, “An evil and adulterous generation seeks after a sign, and no sign will be given to it except the sign of the prophet Jonah. 40 For as Jonah was three days and three nights in the belly of the great fish, so will the Son of Man be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth.

However, whilst the tale of Jonah contains a parallel with the death and resurrection of Christ, it can also be seen as the story of the Christian. After ignoring God’s command to go to Nineveh, Jonah journeys west which, as the setting place of the sun, is symbolic of darkness and that which is away from God. It is at the western part of the known world that Jonah encounters the sea monster and is dragged down into the depths, which represents being held in the captivity of death. At this point of despair in the clutches of the beast, Jonah cries out to God (Jonah 2:2) and the Lord commands the beast to release him. Jonah then heeds the command of the Lord and travels east towards Nineveh. After completing his task, Jonah travails further east, and it is at this eastern point that God creates a ‘leafy plant’ around Jonah to provide him with shade.

Prior to baptism, all of us are slaves to the captivity of death. This is why, in the moments before we are baptised, we stand facing west to renounce the Devil. ‘For the West’, according to St. Cyril of Jerusalem, ‘is the place where darkness appears, and that one [Satan] is darkness and possesses his power in darkness.’ We have cried out to God, and like Jonah, the sea monster has had no choice but to release us. And so, by beginning our lives in Christ at the western most point, and moving eastward towards the altar (the table prepared for us), we hope that when we die, we are found worthy to enter the eastern most point; the ‘green pastures’; Paradise.

The story of Jonah is filled with his reluctance to follow the commands of the Lord. Even when he had found rest in the east, he requested that his life be taken away (Jonah 4:3). How often, like Jonah, do we want to head back towards the west, preferring the comfort of sin to the company of God? Yet, God continually calls us to repentance, and when we respond, the beast is compelled to unbind us. Jonah’s story, then, is clearly an image of our life in Christ. And it is for this reason that the depictions of him relate to the Good Shepherd.

Closing remarks

Here, I return to the catacomb art that sparked this inquiry. We can now see that the ceiling art encapsulates the entire Christian journey and hope. These Christians have died in the hope that they have lived Jonah’s story of repentance and crying out towards God. They have died in the hope that they have heeded the commandments of the Lord. They have died in the hope that, through their participation in the sacramental life of the Church, they may be counted amongst Christ’s sheep and given entry into the ‘green pastures’ of salvation. This is why the images of Jonah converge on the Good Shepherd. Like these Christians, let us hope that we hear Christ when He calls us: ‘My sheep hear My voice, and I know them, and they follow Me. And I give them eternal life, and they shall never perish; neither shall anyone snatch them out of My hand’ (John 10:27-28).

Theo Andreou January 2022

Further Reading

This post is primarily indebted to the following sources:

Chapter 11 in: Danielou, Jean, The Bible and the Liturgy (Notre Dame Press, 1956)

Pagaeu, Jonathan, Jonah – Resurrecting the Body and Saving the City (2014), <Jonah – Resurrecting The Body and Saving The City – Orthodox Arts Journal> [accessed 22 January 2022]