by Theo Andreou

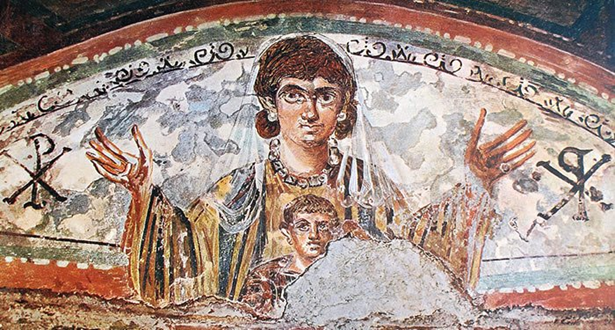

Over one thousand years stands between these two images of the Mother of God tenderly embracing her Son. They testify to the truth of Mary’s own words in Luke 1:48: ‘For behold, from now on all generations will call me blessed…’ The image on the left is from the catacomb of Priscilla in Rome, dating back to the first half of the 3rd century. The image on the right is from the Parekklesion of Chora, Constantinople. It dates to the early 14th century.

Since the beginning of the first millennium, Christians have been captivated with the figure of Mary. But why was she revered so highly by early Christians? This is the question I want to explore below. To excavate the thinking behind their love for the Virgin Mary, I will turn to the hymns, homilies, prayers and icons of the early Church. We will see that their devotion was grounded in both the theological reflection about her role in salvation, and the experience of her powerful intercessions in their lives. The goal of this article is not to provide an exhaustive account of the Marian devotion in the early Church, but rather an entry point. With all that being said, grab a cup of tea, put your feet up, and let’s begin!

From the Shadows: A Typological Approach to Mary

Before I delve into how Mary was perceived by early Christians, I first want to elucidate how the Scriptures were read and interpreted in the early Church. The early exegetes of the Church did not confine themselves to a purely literal reading of the Scriptures. To do so would have been to ignore the hidden truths contained within the text. As St. Ephrem the Syrian (d.373) writes: ‘Anyone who encounters Scripture should not suppose that the single one of its riches that he has found is the only one to exist’. The Scriptures are multivalent, and as such, contain both literal and ‘higher’ meanings without contradiction. Thus, we saw in the previous article, for example, that the Fathers interpreted Psalm 22 (23) as a summation of both the sacraments of initiation and the structure of our life in Christ. We also saw that the story of Jonah was regarded as foreshadowing the death and resurrection of Christ. In both of these cases, the early Christians were reading the Scriptures typologically in order to elicit their hidden meaning.

According to St. John of Damascus (d.749), types are ‘images of the future’ which describe ‘the things to come in shadowy enigmas’. The ‘things to come’ are called antitypes. To illustrate typology, let’s return to the story of Jonah, who remained in the belly of the sea monster for three days before emerging. The Fathers saw this as a type of Christ’s death and resurrection on the third day. By this, it is meant that Christ’s story was already contained within the story of Jonah, but it was obscured. It is only in the light of the risen Christ that when we now read the story of Jonah, we see the story of Christ (Luke 24:27). It is only because we have access to the fulness of Christian revelation that the types within the Old Testament are now discernible. This is why types are often referred to as shadows (Acts 17:1-4; 10-12; Colossians 2:17; Hebrews 8:5-6; Hebrews 10:1).

As we have seen, types silently gesture towards their antitypes. But there is also a sense in which an antitype can be partially present it its type(s). For example, after recounting the tale of Noah’s Ark, where eight people ‘were saved through water’, St. Peter writes: ‘There is also an antitype which now saves us – baptism… through the resurrection of Jesus Christ’ (1 Peter 3:18-22). Through baptism, we cast off our old selves and are ‘born again’ into Life; a life in Christ. Even though baptism occurs at a later point in time chronologically, it is precisely because the waters of baptism are salvific that the ‘eight souls’ in the story of Noah, the type of those being baptised, ‘were saved through water’. Similarly, there is a sense in which the story of Jonah happened because of Christ’s death and resurrection. Thus, it can be said that types can actually embody an aspect of their antitype too.

Being attentive to the typology of Scripture allowed the early Christian writers to see the cohesion between the Old and New Testaments, and how the Old had found its fulfilment in the New. It also allowed them to see the divine plan which had been unfolding since the dawn of time; a plan which involved the Virgin Mary. St. Proclus of Constantinople (d.446) writes: ‘the entire miracle of the Virgin birth is hidden in the shadows’. Going forward, then, we shall see that typology played a crucial role in the Church’s reflection on Mary.

The Recapitulation of Adam and Eve

Some of the earliest meditations on the role of the Mother of God acknowledge Eve as a type of Mary. This line of thought further elaborated upon St. Paul’s conception of Adam as a type of Christ, which we can find in Romans 5:14-15:

Yet death reigned from Adam to Moses, even over those whose sinning was not like the transgression of Adam, who was a type of the one who was to come.But the free gift is not like the trespass. For if many died through one man’s trespass, much more have the grace of God and the free gift by the grace of that one man Jesus Christ abounded for many.

And in 1 Corinthians 15:20-22, we read: ‘But in fact Christ has been raised from the dead, the first-fruits of those who have fallen asleep. For as by a man came death, by a man has come also the resurrection of the dead. For as in Adam all die, so also in Christ shall all be made alive.’

To articulate the saving work of Christ, St. Paul draws a parallel between Adam and Christ, and contrasts the consequences of their actions. Through his transgression, Adam brought death into the world, whereas Christ, through His life, death and resurrection, brought about life. In the 2nd century, after reflecting upon the typological connection between Adam and Christ (as the second Adam), the early Christians extended this parallel to incorporate a typological connection between Eve and Mary, whom they considered to be the second Eve. To evidence this, I want to draw your attention to the following passage from St. Irenaeus of Lyons (c.130-c.202), the spiritual grandson of St. John the Evangelist. In his On the Apostolic Preaching, he writes:

And just as through a disobedient virgin man was struck and, falling, died, so by means of a virgin, who obeyed the word of God, man, being revivified, received life… For it was necessary for Adam to be recapitulated in Christ, that “mortality might be swallowed up in immortality”: and Eve in Mary, that a virgin, become an advocate for a virgin, might undo and destroy the virginal disobedience by virginal obedience.

To grasp at what is going on here, we first need to understand what St. Irenaeus’ means by ‘recapitulation’. According to St. Irenaeus, the fact that humanity was created by an uncreated God necessitates that a gulf existed between them. Starting at this distance from God, Adam and Eve are described as being spiritual children. He writes:

It was necessary for man first to be created, and having been created to grow, and having grown to arrive at manhood, and having arrived at manhood to multiply, and having multiplied to gain strength, and having gained strength to be glorified, and having been glorified to see his own Master. For God is destined to be seen, and the vision of God confers incorruption, and incorruption brings us closer to God.

For St. Irenaeus, Adam and Eve were to make ‘gradual progress’, ‘advancing towards perfection, coming closer, that is to say, to the Uncreated One.’ By following the commandments of God, they were preparing themselves to receive the glory of God in order to commune with Him in a deeper sense, and thereby close the gulf that naturally existed between them. However, by disobeying God, they prevented themselves (and by extension, human nature) from attaining its proper end: deification. Following their transgression, death and corruption were also ushered into the world.

The term ‘recapitulation’, which St. Irenaeus borrows from classical rhetoric, means the ‘conclusion’, or ‘summing up’ of the themes in a speech. Theologically, it refers to the historical moment when the Son of God became incarnate of the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary, as this was the moment which God had known since the beginning of creation, and towards which everything was heading. In short, the recapitulation of the world is its being brought to fulfilment. Through Adam, humanity had failed to enter into communion with divinity. But through Christ, our nature became hypostatically united with the divine nature. Through Adam, death came into the world. Through Christ, Life Himself entered into creation and enabled us once more to assimilate unto God. Again, the type is not merely repeated in the antitype, it is fulfilled.

With all this in mind, I return to the passage from On the Apostolic Preaching, which mentions the recapitulation of Eve in Mary. Here, St. Irenaeus emphasises the culpability of Eve. She was created with free will, and thus had the capacity to draw closer to God, yet chose to be ‘disobedient’. As a direct result of her own volition, humanity ‘was struck, and falling, died’. It was because of her choice that reality was altered and death entered into the world. Correspondingly, it was through the voluntary obedience of Mary towards God that ‘man, being revivified, received life’. Her deliberate obedience to God overturned Eve’s deliberate disobedience. As St. Irenaeus writes elsewhere:

Just as [Eve] was led astray by an angelic word, so that she fled from God, having betrayed his word, so [Mary] received the good news through an angelic word that she might bear God, obedient to his word. For if [Eve] was disobedient to God, [Mary] was persuaded to obey God, so that the virgin Mary became advocate for the virgin Eve. And just as the human race was bound to death by a virgin, so it was saved by a virgin, virginal disobedience being equally balanced by virginal obedience.

Just as Eve played an active role in the condemnation of the cosmos, Mary played an active role in its salvation. Through the second Adam and the second Eve, the gulf between humanity and divinity has finally been closed. To clarify, it is Christ Himself Who effects the salvation of the world, but it was Mary’s ‘yes’ to the Archangel Gabriel that enabled it to happen (Luke 1:38). God never compels us to obey Him. Rather, he seeks to enact our salvation by interacting with us synergistically, because it is in a cooperative relationship that true love resides. Given this, the Incarnation could not have occurred without Mary first giving consent.

The contrast between these two female figures continued to be expressed in the tradition of the Church, both theologically and liturgically, after St. Irenaeus. Once this typological connection between Eve and Mary had been made, it was never forgotten. Beginning his homily on the Theotokos, or ‘God-bearer’, St. Gregory Thaumaturgus (d.c.270) writes, ‘When I remember the disobedience of Eve, I weep. But when I view the fruit of Mary, I am again renewed.’ Later, in the 4th century, St. Ephrem the Syrian composed a hymn with the following verse:

Mary and Eve in their symbols

Resemble a body, one of whose eyes

Is blind and darkened.

While the other is bright and clear,

Providing light for the whole.

And in a sermon delivered by St. Proclus of Constantinople (d.446) in the early 5th century, we find:

Through ears that disobeyed, the serpent poured in his poison;

Through ears that obeyed, the Word entered in order to build a living temple.

We also find this connection being made in the hymns sung by the Orthodox Church to this day. The first Ikos of the Akathist Hymn, composed in the 5th/6th century, dramatises the reaction of the Archangel Gabriel to Mary’s ‘let it be to me according to your word’. Gabriel proclaims:

Hail, Thou through whom joy will shine forth:

Hail, Thou through whom the curse will cease!

Hail, recall of fallen Adam:

Hail, redemption of the tears of Eve!

Here, the Mother of God is honoured precisely because salvation occurs through her. Additionally, we find St. Irenaeus’ emphasis on Mary’s exercise of free will in the hymns sung for The Feast of the Annunciation. To express this, one hymn for Matins, primarily composed by St. Theophanes the Confessor (d.c.850), takes on the form of a dialogue between the Virgin and the Archangel Gabriel. Mary is depicted as receiving Gabriel’s message with hesitation:

My mother Eve, accepting the suggestion of the serpent, was banished from divine delight: and therefore I fear thy strange salutation, for I heed lest I slip.

As the dialogue progresses, Mary discerns the genuine nature of Gabriel’s visitation and accepts his words with gladness. It is at this point she cries out:

May the condemnation of Eve be now brought to naught through me; and through me may her debt be repaid this day. Through me the ancient due be rendered up in full.

To summarise, Mary’s decision not only avoided the mistakes of Eve by testing the spirit that had appeared to her (1 John 4:1), it also reversed the consequences of Eve’s disobedience. This is but one of the reasons that Mary has been revered throughout the history of the Church.

Mother of the Living

Continuing with the connection between Eve and Mary, I want to draw your attention to Genesis 3:20. In the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Old Testament), the name ‘Eve’ is translated literally as ‘Life’ (ζωή): ‘And Adam called his wife’s name Eve; because she was the mother of all living.’ All those who were naturally conceived from this point forth owed their being to her. As Clement of Alexandria (d.c.215) explains, ‘She thus became the mother of the righteous and unrighteous alike’. Very quickly within the history of the Church, as reflection on Mary as the second Eve continued, this phrase was promptly applied to the Virgin Mary. As St. Epiphanius of Salamis (d.403) writes in his Panarion:

She [Mary] is the one who was signified by Eve, inasmuch as she [Mary] was typically given the title ‘mother of the living’… And according to external appearances every birth of men on earth springs from that Eve. Still, in all truth, Life itself has been born to the world from Mary, in order that Mary might give birth to the Living [Christ, in the singular] and that she might become the ‘mother of the living’ [Christians, in the plural]. Mary therefore was called ‘mother of the living’ typically.

Notice that, for St. Epiphanius, the title was originally given to Eve because she typifies Mary. The title was applied to the first Eve in expectation of the second, Mary, who recapitulates the actions of the first. Mary is the true ‘mother of the living’ because she became mother to Life Himself. And according to St. Epiphanius, she is also the ‘mother of the living’ because she became the mother of all those who find life in Christ. To see this, I suggest we turn our attention to a further parallel between Mary and Eve.

Throughout the Gospel of John, Jesus repeatedly refers to Mary as ‘woman’. It is only as He hangs from the cross, with Mary and John beneath Him, that He refers to her as ‘mother’: ‘he said to his mother, “Woman, behold, your son!” Then he said to the disciple, “Behold, your mother!” And from that hour the disciple took her to his own home’ (John 19:27). In Genesis, the ‘woman’ was given the name ‘Eve’ and the title, ‘mother of all living’ by Adam after her expulsion from Eden. At the foot of the cross, in anticipation of the gates of Paradise reopening, Mary, hitherto referred to as ‘woman’, is identified as ‘mother’ by the second Adam. Her attentiveness to the will of God allowed Christ to become incarnate in order to reclaim Paradise for humanity. All those who find eternal life in Christ do so because of Mary’s obedience. For Origen of Alexandria (d.c.253), St. John in the passage above exemplifies what it means to have faith in Christ. He is so alight with love for his God that he follows Him to Golgotha and stands by Him at His death. St. John’s perfect faith indicates that it is not merely him that lives, but Christ in him (Galatians 2:20). For this reason, Origen identifies that Christ does not say, “Woman, behold another son for you in my place”, but “Woman, behold, your son!”, or, as he himself paraphrases it, “this is Jesus whom you bore”. Mary becomes the mother of all those who, like John, live faithfully to Christ.

The notion of Mary as ‘mother of the living’, and the imagery from John 19, are brimming with ecclesial connotations. To give an example, St. Ephrem the Syrian, in a parallel he draws between Moses and Christ, writes that upon the cross, Christ ‘established John, who was a virgin, in place of Joshua, son of Nun. He confided Mary, his Church, to him, as Moses [confided] his flock to Joshua…’ Effortlessly, St. Ephrem marries the Marian with the ecclesial. In the next two sections, I want to delve deeper into the relationship between Mary and the Church. In doing this, another aspect of Mary’s image in the early Church will be revealed.

The Image of the Virgin Mother

According to the Scriptures, Mary, the Mother of God, is both ‘virgin’ and ‘mother’ simultaneously. She is a virgin, and yet through the Holy Spirit, becomes a mother by conceiving Christ in her womb. On the face of it, it only seems fitting to call Mary the ‘Virgin Mother’. Yet, within the 2nd century, we see this term also being applied to the Church. In this section, I first want to explore the rationale behind this appellation for the Church, which, in turn, will allow us to see why the early Christians were theologically justified in knitting the images of Mary and the Church together. To begin our investigation into why the Church was referred to as the Virgin Mother, I turn to the New Testament.

Throughout his epistles, St. Paul conveys his unique relationship to the various Christian communities he addresses by using parental imagery. For example, in 1 Corinthians 4:14-15 we read:

I do not write these things to make you ashamed, but to admonish you as my beloved children. For though you have countless guides in Christ, you do not have many fathers. For I begot you in Christ Jesus through the gospel.

It was through hearing the gospel preached to them by St. Paul that faith was born within them (Romans 10:17). As a spiritual parent to these Christians, St. Paul makes it clear that his task is to nurture and cultivate their faith so that Christ becomes fully present in every believer. Hence, he refers to the Christian community in Galatia as, ‘My little children, with whom I am again in travail, until Christ be formed in you!’ (Galatians 4:19). Through baptism, we are born again in Christ, and must cooperate with Him in order to be more fully conformed to His image and likeness. St. Paul can help these Christians to attain this goal precisely because he has achieved it himself:

I have been crucified with Christ; It is no longer I who live but Christ who lives in me; and the life I now live in the flesh I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me. (Galatians 2:20)

By becoming Christians, we are both ‘the body of Christ and individually members of it’ (1 Corinthians 12:27). All those who were baptised ‘by the one Spirit were baptised into the one body’ (1 Corinthians 12:13), and as such, are expected to live in submission to the head, Christ.

Christ is ‘the head over all things for the Church, which is his body, the fullness of him who fills all’ (Ephesians 1:22-23). In Ephesians 5, St. Paul remarks that Genesis 2:24, which mentions that a man shall leave his parents to join his wife and ‘become one flesh’ with her is actually a reference ‘to ‘Christ and the Church’ (Ephesians 5:32). Given this, he tells the Christians in Corinth: ‘I betrothed you to one husband, to present you as a pure virgin to Christ’ (2 Corinthians 11:2). Clearly, then, St. Paul envisages our acceptance of the gospel through baptism as our birth as Christians. By leading a pleasing life to God, Christ becomes more fully present within us. And by virtue of His presence, we receive the right to be called children of God (John 1:12), able to call upon God as “Abba! Father!” (Galatians 4:6).

With all of the scriptural imagery outlined above, we unsurprisingly find that as early as the 2nd century, the Church was widely referred to as ‘Virgin Mother’. The Shepherd of Hermas, which some Christians regarded as scripture, describes a series of visions in which the Church appears to Hermas as a woman. She first appears as an old woman because, ‘she was created the first of all things’, ‘and for her sake the whole world was established’. As the visions continue, she gradually becomes younger, before finally appearing as a young maiden, ‘“adorned as if coming forth from a bridal chamber”, all in white and with white sandals, veiled to her forehead, and a turban for a headdress, but her hair was white’. Here, the Church becomes the pure and spotless virgin which St. Paul talks about presenting to Christ (2 Corinthians 11:2-4). She is a virgin, and yet at the same time addresses the Christians in Rome as her ‘children’.

A similar notion appears in Clement of Alexandria’s Paedagogus: ‘There is one Father of all, there is one Word of all, and the Holy Spirit is one and the same everywhere. There is also one Virgin Mother, whom I love to call the Church’. But it is in The Letter of the Churches of Vienne and Lyons, preserved in Eusebius’ Church History, that the identification of the Church as ‘Virgin Mother’ is most elaborated. The letter recounts the sufferings of Christians in Gaul in the year 177; many of whom were described as being ‘unable to endure such a great conflict’, and as such were labelled as ‘stillborn’ or ‘miscarried’. Yet Blandina, a young slave girl who was spread-eagled on a post, prayed fervently and encouraged them to persevere. Because of her spiritual strength, they ‘saw with their outward eyes in the person of their sister the One who was crucified for them’. Consequently, their sufferings:

were neither idle nor fruitless; for through their perseverance the infinite mercy of Christ was revealed. The dead were restored to life through the living; the martyrs brought favour to those who bore no witness, and the virgin Mother experienced much joy in recovering alive those whom she had cast forth stillborn. For through the martyrs those who had denied the faith for the most part went through the same process and were conceived and quickened again in the womb and learned to confess Christ…

Here, we can see that by remaining faithful to Christ, the Church, as Virgin Mother, conceives them again in her womb in order to give birth to them as children of God through martyrdom.

This letter may have been written by St. Irenaeus, who writes elsewhere that it is through the Virgin Mary that Christians receive a new birth. According to him, the Old Testament prophesied, ‘that the Word would become flesh, and the Son of God the Son of man – the pure one opening purely that pure womb which regenerates human beings unto God…’ Similarly, Didymus of Alexandria (d.c.398) compares Mary’s womb to the waters of baptism, because through baptism we become ‘one body’ with the One Who was contained within her womb. He writes, ‘For [Mary] is the baptismal font of the Trinity, the workshop of salvation of all believers; and those who bathe therein she frees from the bite of the serpent and she becomes mother of all…’ For the first few centuries of the Church, it is clear that the image of ‘Virgin Mother’ was attached to both Mary and the Church. The same can be said for various other images, including that of ‘second Eve’, as in De Anima, Tertullian (c.155-c.220) asserts: ‘If Adam was a type of Christ, Adam’s sleep was [a type] of the death of Christ who had slept in death. Eve coming from Adam’s side is a type of the Church, the true mother of all living.’

It seems, then, that there were two strands of thought (pertaining to Mary and the Church) running in parallel, each quietly invoking the other. Whilst both are tantalising close to touching at times, the connection is never made explicit until the 4th century.

Mary: She Who Listens

Recall that of her own accord, Mary accepted the will of God at the Annunciation. Her faith in God, and her love for Him, allowed her to receive God Himself in her womb. Throughout the Gospels, her receptivity to the will of God continued to be evidenced after Gabriel’s visitation. In Luke 2:51, for example, after a young Jesus had spoken in the Temple, Mary is depicted as the one who receives the teachings of Christ most earnestly: ‘And his mother treasured up all these things in her heart’. Time and time again, Mary is presented as the most attentive person to the will of God; she is paradigmatic of how we should respond to the will of God in our own lives. And as one who receives God in herself and is attentive to His words, it is not difficult to see a connection between her and the Church. Picking up on this symbolic correlation in the 4th century, St. Ephrem the Syrian asserts:

The Virgin Mary is a symbol of the Church, when she receives the first announcement of the gospel. And, it is in the name of the Church that Mary sees the risen Jesus. Blessed be God, who filled Mary and the Church with joy. We call the Church by the name of Mary, for she deserves a double name.

All four Gospels attest that Mary Magdalene was the first to witness the risen Christ, not Mary, the Mother of God. Yet here, the latter usurps the place of the former. The same can be seen in another of St. Ephrem’s hymns. He writes:

Three angels were seen at the tomb:

These three announced that he was risen on the third day.

Mary, who saw him, is the symbol of the Church

which will be the first to recognise the signs of his Second Coming.

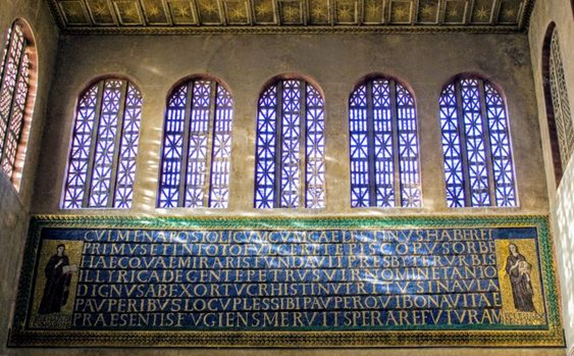

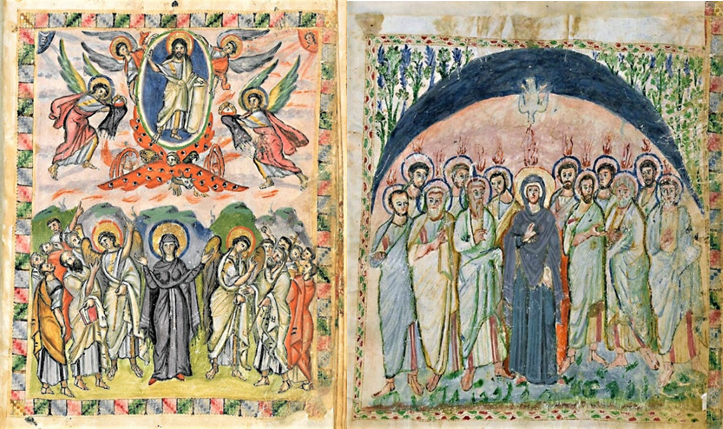

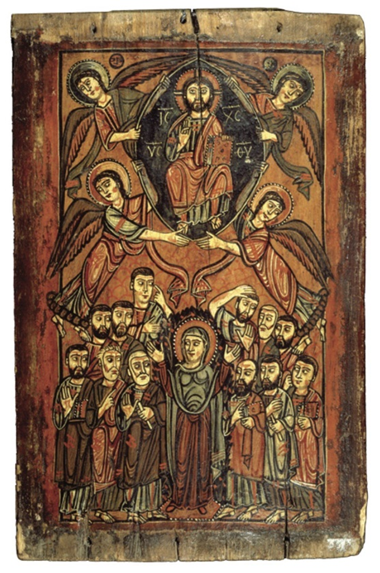

St. Ephrem is not interested in laying out the ‘historicity’ of the event. Rather, he is concerned with conveying the event’s theological reality. Thus, it is precisely in the Mother of God’s capacity as a symbol of the Church that she is depicted as the first witness to the risen Christ. This theological truth continued to find expression in the Church’s hymnography. Two centuries later, St. Romanos the Melodist composed a kontakion On the Lament of the Mother of God, which portrays Christ reassuring His mother that she will be the first to see Him again after His resurrection: ‘When he heard this, the One who knows all things before their birth answered Mary, “Courage, Mother, because you will see me first on my coming from the tombs.’ This theological truth also found expression in the artistic tradition of the Church in the 6th century. The Rabbula Gospels (586), found in the Monastery of St. John of Zagba, Syria, are filled with vibrant illustrations of biblical events.

The images of the Ascension and Pentecost both regard Mary, the Mother of God, as a central figure (again, invoking her connection with the Church). But of interest to the subject of her witnessing the risen Christ first, I want to draw your attention to the image below, which is the bottom half of an illustration which also depicts the Crucifixion. Here, whilst Mary Magdalene is present, she recedes into the background, obscured by Mary, the ‘Virgin Mother’.

Again, like with the symbolism of Eve, once the connection between Mary and the Church was made, it was never erased. Though interestingly, the personification of the Church as a woman independent of Mary did diminish by the middle of the 5th century. We glimpsed at the beginning of this process in the 4th century with St. Ephrem, but it was in the 5th century that the theological imagery surrounding the Church, such as ‘Virgin Mother’ and ‘Mother of all living’, was taken on almost entirely by the Virgin Mary. Perhaps the affirmation of the Marian title Theotokos, or ‘God-bearer’, at the Council of Ephesus (431) played a part in finally consummating the marriage between the Marian and the ecclesial.

Further, it is remarkable that the volume of Marian interpretations of the Old Testament increased exponentially in the 5th century too. From what we have seen so far, to declare that these Marian types were constructed or made up at this time is simply incorrect. Rather, it makes more sense to assume that as the obvious connection between her and the Church became more explicit, the typological references that had been used and compiled for the Church were transferred wholesale to Mary. Far from being arbitrary, this occurred because Mary’s role in the symbolic world does indeed point to all of the same themes that we have seen applied to the Church; she embodies the ekklesia.

The ‘God-bearer’

By now, I hope that I have made the connection between Mary and Eve, and Mary and the Church clear. In what follows, I want to focus on the typological connections which relate to Mary’s role as Theotokos. This title, as mentioned previously, was ecumenically affirmed at Ephesus in 431 (though the earliest recorded use of it predates Ephesus by at least a century). Though Theotokos is a Marian epithet, it actually serves to protect the salvific reality of Christ’s incarnation. As St. Gregory of Nazianzus (d.c.390) aptly remarks, ‘The unassumed is the unhealed, but what is united with God is also being saved.’ Christ had to become fully human in order to recapitulate every aspect of our disposition. He had to have a human body, soul, mind and will; and He had to be born and die in order for the entire human condition to be saved. It is only by accepting that God became fully man whilst retaining His divinity that salvation is possible. Referring to Mary as the ‘God-bearer’ safeguards this Christological and soteriological truth. She is the one in whom God incarnate resides, and as such, is the one through whom salvation came into the world. Hence, after acknowledging Mary as ‘the one who contains the uncontainable’, in her ‘holy virginal womb’, St. Cyril, in a homily delivered at Ephesus, proceeds to refer to her as the one:

through whom heaven is exalted, through whom angels and archangels are delighted, through whom demons are banished, …through whom fallen human nature is assumed into heaven, …through whom holy baptism came into being for all faithful, …through whom the churches have been founded for all the world, …through whom the dead were revived… Is it even possible for people to speak of the celebrated Mary? The virginal womb; O thing of wonder! The marvel strikes me with awe!

Most of the Marian types in the Old Testament point to the paradox of her containing the Uncontainable One in her womb. By the time of St. John of Damascus (d.749), many of these shadows had been brought to light through homilies, hymns and icons. Drawing on the Church’s rich tradition, St. John, in his first homily On the Dormition, writes:

You are the royal throne, around which the angels stand to see their Lord and creator seated upon it. You are called the spiritual Eden, holier and more divine than that of old; for in the former Eden the earthly Adam dwelt, but in you the Lord from heaven. The ark prefigured you, in that it guarded the seeds of a second world, for you gave birth to Christ, the world’s salvation, who overwhelmed <the flood of> sin and calmed its waves. The burning bush was a portrait of you in advance; the tablets written by God described you; the ark of the law told your story; the golden urn and the candelabrum and table, the rod of Aaron that had blossomed – all clearly were foreshadowings [of you].

This list is by no means exhaustive, but it offers us a glimpse at some of the typological references to Mary as Theotokos that the Church had picked up on by the 8th century. Notice that all of these examples are places where God was encountered. Some of them are also places where God was worshipped, and as such, were treated with reverence. For example, in the presence of the burning bush, Moses was told: “Do not come near; take your sandals off your feet, for the place on which you are standing is holy ground” (Exodus 3:5).

The same can be said of the Ark of the Covenant. The Ark was the holiest object of the Temple, and was located in the Holy of Holies – the innermost sanctum of the Temple that the High Priest could only enter once a year on the Day of Atonement. It was overlayed with pure gold, and a ‘mercy seat’ of pure gold sat on top of it, upon which were two golden Cherubim. Like the burning bush, the Ark was holy because the presence of God was encountered there:

There I will meet with you, and from above the mercy seat, from between the two cherubim that are on the ark of the testimony, I will speak with you about all that I will give you in commandment for the people of Israel. (Exodus 25:22)

These objects were revered because they were places where God manifested Himself. For this reason, St. Proclus asserts that, ‘Mary is venerated [Προσκυνεῖται] for she became a mother, a servant, a cloud, and the ark of the Lord.’ But as we have mentioned, types are merely shadows of their antitypes. In Mary, then, the fullness of the type is revealed. God does not simply reveal Himself through her as with the bush and the Ark. Rather, the fullness of God’s divinity dwells hypostatically within her! If the ground around the bush was rendered holy on account of God’s brief manifestation, how much holier must Mary be, who carried Him for nine months inside her womb. And further, whilst Mary is a place of God, she is also more than that. She is not a passive dwelling place of God; she is the one who said “yes” to Him and voluntarily became His mother. Again, her cooperation with God is an important part of why she is so highly honoured in the early Church.

The image of the Ark of the Covenant is one of the earliest Marian types recognised by the Church. We have already seen it in the writings of St. Proclus in the 5th century, but it is also present in the 4th century. St. Ephrem, for example, writes, ‘The symbol of you is to be found, O Virgin, in the covenant Ark; in prophecy was your fair image depicted and placed in the Scriptures for him who is discerning…’ In fact, this typological connection stretches right back to the first century. After the Annunciation, the Gospel of Luke states:

In those days Mary arose and went with haste into the hill country, to a town in Judah, and she entered the house of Zechariah and greeted Elizabeth. And when Elizabeth heard the greeting of Mary, the baby leaped in her womb. And Elizabeth was filled with the Holy Spirit, and she exclaimed with a loud cry, “Blessed are you among women, and blessed is the fruit of your womb! And why is this granted to me that the mother of my Lord should come to me? For behold, when the sound of your greeting came to my ears, the baby in my womb leaped for joy. And blessed is she who believed that there would be a fulfilment of what was spoken to her from the Lord.” (Luke 1:39-45)

Throughout this passage, St. Luke is drawing a parallel to the language surrounding the Ark in 2 Kingdoms (2 Samuel). Both Mary and the Ark are on a journey. In the presence of Mary, Elizabeth’s ‘baby leaped in her womb’. In the presence of the Ark, David dances before it (2 Kingdoms 6:14). David remarks, ‘How can the ark of the Lord come to me?’ (2 Kingdoms 6:9), whilst Elizabeth remarks, ‘And why is this granted to me that the mother of my Lord should come to me?’ The Ark ‘remained in the house of Obed-Edom the Gittite for three months’ (2 Kingdoms 6:11); Mary ‘remained with her [Elizabeth] about three months’ (Luke 1:56).

St. Luke also draws a parallel between Mary and the Tabernacle. After inquiring how she could become pregnant without a man, the Archangel Gabriel replies with, ‘The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you.’ (Luke 1:35) Most of the Old Testament quotations in the New Testament are from the Septuagint, so St. Luke would have been intimately familiar with it. He uses a Greek word, here translated as ‘overshadow’, which only occurs in one other place throughout the entirety of the Old Testament. It is found in Exodus 40:33-35: ‘And Moses was not able to enter into the tabernacle of testimony, because the cloud overshadowed it, and the tabernacle was filled with the glory of God.’ Clearly, since the earliest proclamation of the Gospel, we can see that Mary was regarded as the true Ark and the true Tabernacle; types which serve to symbolically describe the ineffable mystery in her womb. To repeat the words of St. Cyril, ‘The virginal womb; O thing of wonder! The marvel strikes me with awe!’

In what follows, I want to briefly look at how Mary being the Theotokos affects where she belongs in the order of created beings. According to the Scriptures, there are a variety of different angels, such as Dominions, Powers and Principalities. Out of all the angelic ranks, the Seraphim and the Cherubim are described as being the closest to God. In a prayer, Hezekiah exclaims that God is ‘enthroned between the cherubim’ (Isaiah 37:16); an image which is replicated by the golden Cherubim on the Ark. And Isaiah, in a vision, ‘saw the Lord sitting upon a throne, high and lifted up…Above him stood the seraphim. Each had six wings: with two he covered his face, and with two he covered his feet, and with two he flew’ (Isaiah 6:1-2). Around the Throne of God, they continually offer praises, singing, ‘“Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of hosts; the whole earth is full of his glory!” (Isaiah 6:3). The Seraphim, as those constantly in the presence of God, shroud themselves from the blinding fullness of His divinity. It is too much to bear even for them. Yet, through the Incarnation, the fullness of divinity resides in Mary and she is not consumed. As St. Ephrem writes:

In her womb Fire resides,

in her bosom is a mighty wonder:

she grasps this Fire in her fingers,

and in her lap she carries the burning Sun:

how awesome it is to tell of this!

Through the Incarnation, Mary becomes the closest created being to God, and as such, becomes the most exalted of all creation. As one hymn puts it:

It is truly right

to bless thee, O Theotokos

the ever blessed, and most pure,

and the Mother of our God.

More honourable than the Cherubim,

and beyond compare more glorious than the Seraphim,

who without corruption gavest birth to God the Word,

the true Theotokos,

we magnify thee.

This hymn (the ‘Axion Estin’) is still sung in the Orthodox Church today. The first part was composed in the 10th century, whilst the latter half was composed in the 8th by St. Cosmas the hymnographer (d.773). This exalted view of Mary finds its expression throughout countless hymns, homilies, prayers and icons. St. Proclus calls her, ‘the truly radiant cloud, which bore in a body him who thrones above the Cherubim’. And an anonymous prayer, which roughly dates to the 9th century, refers to Mary as, ‘the fiery Throne of God, more glorious than the four heavenly creatures seen by the prophet Ezekiel’. She is ‘above the cherubim, incomparably more glorious than the seraphim, and more honourable than the whole of creation’. Interestingly, the author of this prayer identifies that Mary’s unique position before God as the Theotokos affords her a unique position as an intercessor before Him. Thus, after describing Mary as the pinnacle of all creation, the author writes:

I know your Only-begotten Son is pleased by your prayers and requests. And he is bound under obligation to honour you, since He Himself said: “Honour your father and your mother,” and He will fulfil this obligation to you because He Himself loves His servants, and freely chose to live among them, and it was you who enabled Him to do this, by serving His ineffable birth.

It is precisely because of her role as Theotokos and Mother of God that her supplications are so valued and sought after by the author. However, this is not something novel to the 9th century. In fact, the oldest known prayer to Mary, which dates from the 3rd to the early 4th century, implores her for help as the Theotokos:

Beneath thy compassion,

We take refuge, O Theotokos:

do not despise our petitions in time of trouble:

but rescue us from dangers,

only pure, only blessed one.

Mary as a Refuge

As we saw at the end of the previous section, Christians throughout the first millennium have sought refuge under the protection of the Mother of God. In what follows, I want to highlight three documented examples of Mary’s involvement in the lives of early Christians.

1) The Anastasia

Under the Emperor Valens, who ruled from 364-378, Nicene orthodoxy faced constant attack throughout the Empire. He was an adherent to Arianism (which denied that the Word of God was divine), and used his power to successfully establish Arian clergy. Orthodox clergy were often ousted, and by the time of his death in 378, Constantinople was dominated by Arianism. In 379, St. Gregory of Nazianzus ventured into Constantinople, and immediately converted his cousin’s villa into a church. He named it ‘Anastasia’, as it was to be the place where Nicene orthodoxy was resurrected. According to Theodore Lector’s Tripartite History (composed in the early 6th century):

Gregory the Theologian was then leader of the church in Constantinople, and if he had not called back the city first, it would have been completely filled with the shame of Arius and Eunomius. And the heretics occupied all the churches except the chapel of Anastasia…

This is also confirmed by Sozomen’s Ecclesiastical History, written around 440/443. In Book VII, he writes, ‘The Arians, under the guidance of Demophilus, still retained possession of the churches’. St. Gregory alludes to this struggle in an autobiographical poem, called the Carmen de se ipso, or ‘Song Concerning One-self’, which he wrote towards the end of his life. In it, he cites Exodus on multiple occasions, and refers to his opponents in Constantinople as the oppressive Egypt. He also refers to the Anastasia as a ‘tent’, recalling the image of the Israelites wandering the wilderness. Evidently, the Anastasia stood as the only bastion of orthodoxy in a capital engulfed by Arianism. With this in mind, I want to turn your attention back to Book VII of Sozomen’s Ecclesiastical History. It records that the Anastasia church:

became one of the most conspicuous in the city, and is so now, not only for the beauty and number of its structures, but also for the advantages accruing to it from the visible manifestations of God. For the power of God was there manifested, and was helpful both in waking visions and in dreams, often for the relief of many diseases and for those afflicted by some sudden transmutation in their affairs. The power was accredited to Mary, the Mother of God, the holy virgin, for she does manifest herself in this way.

It is remarkable that the Anastasia, the only orthodox Church in Constantinople, became famous for the countless miracles performed there; all of which were attributed to the Virgin Mary. Additionally, Sozomen’s assertion that Mary ‘does manifest herself in this way’ implies that the Virgin’s involvement in the lives of Christians was a commonplace reality by the mid-5th century.

2) The Theological Assistant

In his Life on St. Gregory the Wonderworker (‘Thaumaturgus’), St. Gregory of Nyssa (d.c.395) remarks that amidst the tumult of heresy, his namesake received a divine revelation, granting him an exposition of the true faith. I will relay what St. Gregory of Nyssa writes below.

Whilst lying awake in bed, someone appeared to the Wonderworker ‘in human form, aged in appearance, clothed in garments denoting a sacred dignity, with a face characterised by a sense of grace and virtue.’ This mysterious figure ‘told Gregory that he had appeared by divine will, because of the questions that Gregory found ambiguous and confusing, to reveal to him the truth of pious faith.’ The figure:

then held up his hand, as if to point out, with his index finger, something that had appeared opposite him. Gregory, turning his gaze in the direction indicated by the other man’s hand, saw before him another figure, which had appeared not long before. This figure had the appearance of a woman, whose noble aspect far surpassed normal human beauty. Gregory was again disturbed. Turning away his face, he averted his glance and was filled with perplexity; nor did he know what to think of this apparition, which he could not bear to look upon with his eyes. For the extraordinary character of the vision lay in this: that though it was a dark night, a light was shining, and so was the figure that had appeared to him, as if a burning lamp had been kindled there.

Although he could not bear to look upon the apparition, Gregory heard the speech of those who had appeared, as they discussed the problems that were troubling him. From their words, Gregory not only obtained an exact understanding of the doctrine of the faith but also was able to discover the names of the two persons who had appeared to him, for they called each other by name.

For it is said that he heard the one who had appeared in womanly form exhorting John the Evangelist to explain to the young man the mystery of the true [faith]. John, in his turn, declared that he was completely willing to please the Mother of the Lord even in this matter and that this was the one thing closest to his heart.

Already in the 4th century, then, Mary’s intercessory power appears to be an appreciated reality of orthodox Christian communities. Interestingly, St. John and the Virgin have been known to appear at other times of confusion in the history of the Church. The most recent known instance transpired in the life of St. Paisios the Athonite (d.1994).

3) The Protectress of Constantinople

In the summer of 626, the Avars allied themselves with the Persians and began to lay siege to Constantinople whilst the emperor Heraclius (d.641) and a vast amount of his army were in Mesopotamia. A homily written shortly after the siege, attributed to Theodore Synkellos, tells of how, ‘The enemy tribes thus encircled the city on the East and on the West, by the sea and on the North.’ Despite constant attacks for over a month, the people remained safe inside the city walls. During the siege, the Patriarch Sergius (d.638) led a procession along the western walls and placed icons of the Virgin with the Christ-child on the western doors of the city. According to Theodore, the people also joined him in prayer:

the city begged in tears the Virgin by the words of the inspired mouth of the archpriest [Sergius]: ‘Save me, oh Lady, save me, because I will perish. Do not remain dumb, inactive, silent any longer, because I know that you are powerful.”

For Theodore, the combined prayer of the people, ‘was a weapon, sabre and shield for all the inhabitants of the city.’ The Patriarch was convinced that the Constantinopolitans would overcome their aggressors, ‘Because the Lord himself fights for us, and because the Virgin Theotokos will also be the champion for this city, if we ourselves turn toward them with all our heart and a devoted soul’.

The Mother of God was seen as the city’s ‘protection’. And according to the 7th century poet, George of Pisidia, she was the city’s ‘General’. Eventually, after two failed naval attacks, the assailants withdrew all of their forces. Upon their departure, they laid waste to the city’s surroundings, including multiple churches. However, in Blachernae, all churches were sacked except one, which happened to be dedicated to the Virgin. For the inhabitants of the city, the victory was clearly the work of the Mother of God, who, according to various accounts, was also seen patrolling the perimeter of the city. Out of appreciation for her intervention, a prooemium for the Akathist Hymn was composed:

To Thee, the Champion Leader, we Thy servants dictate a feast of victory and of thanksgiving as ones rescued out of sufferings, O Theotokos; but as Thou art one with might which is invincible, from all dangers that can be do Thou deliver us, that we may cry to Thee:

Rejoice, Thou Bride Unwedded!

From the early 7th century onwards, Mary became known as the Protectress of Constantinople, and would also be continually invoked as such. The most famous instance of her intervention occurred in the early 10th century. Whilst under siege, the court gathered in the Blachernae chapel to pray. There, St. Andrew the Fool saw the Mother of God holding a veil over the Imperial city, signifying that she would preserve it from harm. This is an event still commemorated today in the Orthodox Church.

An Early Witness to Marian Devotion

In this section, I want to rewind back to the second century to look at another important witness to early Marian devotion; the Protevangelium of James, which means ‘Gospel of the first [years]’.

In it, the author (writing pseudonymously) recounts the story of Joachim and Anna’s struggle to conceive a child. After fervently imploring God, He listens to them and Mary is conceived. It then tells of Mary being dedicated to the Temple, follows her life up to the Annunciation, and describes what happens after. Whilst not all details of this text were accepted as truth, some parts of it were, which indicates that there was already an underlying tradition behind the text circulating within the Church. Regardless, the text was extremely popular and quickly became disseminated throughout the known world. It was translated from Greek into Ethiopic, Syriac, Georgian, Sahidic, Armenian and probably even Latin too. Origen and Clement of Alexandria mentioned it in their writings, and St. Epiphanius of Salamis and St. Gregory of Nyssa actually cited from it.

The Protevangelium is filled with theological assertions about Mary. For example, the text tells of Joachim requesting ‘the daughters of the Hebrews that are undefiled’ to escort Mary ‘into the Temple of the Lord.’ Reading this, the daughter mentioned in Psalm 44(45), who is accompanied by a host of virgins, comes to mind. The Psalm also depicts the daughter approaching the palace of the king; which further invokes the image of Mary being presented to Christ, the bridegroom, as the spotless ‘Virgin Mother’ and ekklesia.

To highlight the Virgin’s own purity and holiness, throughout the text, a constant parallel is drawn between Mary and the Temple. Her own purity is what enables her to receive the God of all in her womb. This parallel reaches its climax when Gabriel appears to Mary as she spins scarlet and purple cloth for the veil of the Temple. Here, an allusion to Hebrews 10:20, which refers to Christ’s flesh as the Temple curtain, is unmissable. Picking up on this, St. Proclus proclaims that Mary became ‘an awesome loom of the divine economy upon which the robe of union [between divinity and humanity] was ineffably woven’.

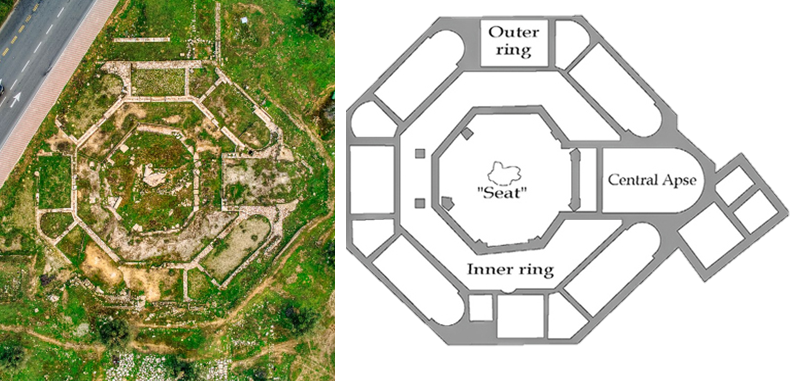

Given the popularity of this text, it is unsurprising that its narrative influenced the construction of various churches. One example is the Kathisma church situated halfway between Jerusalem and Bethlehem. According to the Protevangelium, it was at the halfway point from Jerusalem to Bethlehem that Mary had to rest (‘kathisma’ means ‘seat’) on her journey.

The church was believed to be lost to history until its remains were accidentally discovered during the formation of a new highway. The Armenian lectionary, compiled between 412-439, mentions this site. And whilst the outer octagonal structure was constructed shortly after the Council of Chalcedon (451), the wall around the ‘seat’, in accordance with the lectionary, does date back to the early 5th century. Another example of thenarrative’s influence can be seen in the mosaics of the Santa Maria Maggiore, assembled sometime around 432, at the behest of the bishop of Rome.

This fresco depicts the Annunciation with elements from the Protevangelium. We can see that the Holy Spirit, represented as a dove, descends upon Mary whilst she is creating the veil for the Temple. The same mosaic also depicts St. Joseph holding a rod, which, according to the Protevangelium, played a role in his assumption of responsibility over Mary.

The mosaics within the Santa Maria Maggiore also pull together some of the other Marian themes we have seen so far. Notice that Mary, in the mosaic above, is dressed majestically; adorned in dazzling regal garments. Yet, she is not the only woman depicted in such attire. The fresco below shows the wedding of Rachel and Jacob:

This scene contains a depiction of Pharoah’s daughter:

And here, the wedding of Zipporah and Moses is portrayed:

The women look similar to Zipporah in the mosaic above (as the men do to Moses) because, according to Roman tradition, the unmarried friends of the bride and groom wore similar clothes as they escorted the couple. Given the artistic similarity, it is clear that the mosaics are making a theological assertion. I will try to unravel this below.

In his Dialogue with Trypho, St. Justin Martyr (d.c.165) writes:

The marriages of Jacob were types of that which Christ was about to accomplish. For it was not lawful for Jacob to marry two sisters at once. And he serves Laban for [one of] the daughters; and being deceived in [the obtaining of] the younger, he again served seven years. Now Leah is your people and synagogue; but Rachel is our Church.

For St. Justin, Rachel typifies the Christian Church. This idea is also taken up by St. Cyril of Alexandria, who refers to both Rachel and Zipporah as types of the Church of the Gentiles. Perhaps Mary, then, is presented in the same attire as them because she, as one who embodies the ekklesia, is a bride.

But what about the link to Pharoah’s daughter? To see this connection, let’s turn to St. Athanasius (d.373). In his Letter to Marcellinus, he connects the verse, ‘Hear, O daughter, and consider, and incline your ear’ (Psalm 44[45]:10) with Gabriel’s, ‘Hail, O favoured one’ (Luke 1:28). Given this, he tells us to, ‘Take note that Gabriel calls Mary by name, since he is dissimilar to her in terms of origination, but David the Psalmist properly addresses her as ‘daughter’, because she happened to be from his seed’. Perhaps it is as the royal daughter of the king that Mary links to Pharoah’s daughter. Throughout these mosaics, connections to the Protevangelium and Psalm 44(45) are plenteous. Around the beginning of the 5th century, Mary began to be seen as the ‘queen’ of the Psalm too. This might explain why she is presented in golden robes: ‘at your right hand stands the queen in gold of Ophir’ (Psalm 44[45]:9).

Mary: In the Light

The Santa Maria Maggiore and the Kathisma were two of, but not the only, churches dedicated to Mary in the early 5th century. At least three other major Constantinopolitan churches were built in honour of the Theotokos under the patronage of the empress Pulcheria (d.453). These were the churches of the Theotokos Chalkoprateia, the Theotokos of Blachernae, and the church and monastery of Hodegon. By the end of the 5th century, several relics of the Virgin were transported to these churches from Jerusalem, including her belt and robe/funeral shroud. The Council of Ephesus (431) also took place in a cathedral dedicated to the Theotokos.

In addition to churches and relics associated with Mary, from the end of the 4th century to the beginning of the 5th, several feast days in honour of the Virgin were being celebrated throughout the Christian ecumene. The churches in Syria and Constantinople, for example, kept a feast day for the Theotokos on the day either before or after December 25. For the Christians in Jerusalem, Mary was commemorated on August 15. Under the Emperor Justinian (d.565), the feasts of the Annunciation, the Presentation of the Lord, the Conception of the Theotokos and the Nativity of the Theotokos received a fixed date on the liturgical calendar. And with Emperor Maurice, who reigned from 582 to 602, August 15 became the fixed date for all churches to celebrate the Dormition of the Mother of God. The original feast day in Jerusalem was thus moved to August 13.

It is as if, by the 6th century, all shadows surrounding the figure of Mary had been dispelled. The importance of the Theotokos was now in the light for all to see. So bright was her figure as ‘Virgin’, ‘Mother’, ‘Theotokos’, ‘second Eve’, ‘intercessor’ and ‘Protectress’ that her image became commonplace throughout the Byzantine Empire and beyond. Rings, brooches, bracelets, seals, silks, tapestries and coins all bore witness to Mary’s significance. I will share a few examples below.

All of these Byzantine seals depict Mary with the Christ-child. The leftmost seal was produced sometime between 610 and 641. The seal in the centre was crafted between 717 and 720, and the one on the right was made during the episcopate of St. Photios (d.893). On the back, the rightmost seal bears the inscription: ‘Theotokos, help your servant Photios, archbishop of Constantinople, the New Rome.’ I have only shared three examples here, but there are numerous others that survive to this day.

Made between the 6th-7th centuries, this golden ring depicts the Annunciation, and bears the inscription, ‘Hail, O favoured one, the Lord is with you!’ (Luke 1:28).

This bracelet, produced in Egypt around the year 600, presents the Virgin in the orans posture, as one who prays and intercedes. All of these objects testify to the fact that Mary’s significance did not solely find expression in the theological proclamations of the Church. She had permeated into every fibre of Byzantine culture and engraved herself into the minds and hearts of people from all over the world.

Closing Remarks

At the end of this exploration, we can now see why Mary, the Mother of God, was revered so highly in the early Church. To summarise briefly, countless types silently bore witness to the mystery that occurred in her womb, which she allowed to happen by her own free will. As one who was completely receptive to the will of God, she became a powerful symbol of the Church, and provided all Christians with an example to follow. Indeed, it was through her complete obedience to God that the disobedience of Eve was recapitulated. Further, it is through the Incarnation that she became the Mother of all the faithful, and the most exalted being in all of creation. As such, she is the greatest intercessor we have before her Son.

We have seen that Mary was not just exalted by the early Christians for theological reasons, but because they actually felt her presence in their lives. It was because of this active involvement in the lives of the faithful that churches were built in her honour, her relics were treated with the utmost reverence, and several feast days were established to celebrate her. These facts were not just local to certain areas: devotion to Mary was everywhere! And by honouring Mary as the Theotokos, the Church realised that they were safeguarding Christological orthodoxy. Mary is honoured for precisely who she is in relation to her Son; she points the way for us to move towards Him, and holds our hand along the way. All of the themes discussed in this article have remained in the liturgical consciousness of the Orthodox Church and are still hymned today!

So, next time you are in Church singing hymns to the Mother of God, remember that you are standing on the consolidation of two thousand years of Church experience and life. Since the beginning of the first millennium, Christians have not only encountered Mary typologically in the Scriptures, but have felt her prayer and power as an intercessor before God in their own lives as they struggle towards their salvation. Thus, in harmony with our Christian forebearers, let us sing:

All the creation joins the angel Gabriel, crying out to the Theotokos in fitting song: Hail! undefiled Mother of God. Through thee we have been delivered from the ancient curse and have become partakers of incorruption.

O Holy of Holies and pure Mother of God, Mary, from the snares of the enemy and from every heresy and affliction, at thine intercessions set us free who venerate with faith the ikon of thy holy form.

Far greater than the cherubim, high above the seraphim, and more spacious than the heavens, art thou shown forth, O Virgin, for thou hast contained in thy womb our God whom nothing can contain, and hast ineffably borne Him: entreat Him earnestly on our behalf. (Canticle 9, Matins, The Entry of the Most Holy Theotokos into the Temple)

Further Reading

This article has been written with the help of some excellent authors. I will list the texts I drew from below:

Banev, Krastu, “Myriad of Names to Represent Her Nobleness’: The Church and the Mother of God in the Psalms and Hymns of Byzantium’, in Celebration of living theology: a festschrift in honour of Andrew Louth (London: Bloomsbury, 2014)

Behr, John, The Mystery of Christ: Life in Death (SPCK, 2006)

Brock, Sebastian, Bride of Light: Hymns on Mary from the Syriac Churches (St. Ephrem Ecumenical Research Institute, 1994)

Cunningham, Mary B., Gateway of Life: Orthodox Thinking on the Mother of God (SVS Press, 2015)

Hart, Aidan, Festal Icons: History and Meaning (Gracewing, 2022)

Lidova, Maria, ‘The Imperial Theotokos: Revealing the Concept of Early Christian Imagery in Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome’, Convivium 2 (2) (2015) 60-81

Louth, Andrew, ‘John of Damascus on the Mother of God as a Link between Humanity and God’, in The Cult of the Mother of God in Byzantium: Texts and Images, ed. by L. Brubaker and Mary B. Cunningham (Farnham: Ashgate, 2011)

— ‘Mary the Mother of God and ecclesiology: some Orthodox reflections’, International Journal for the Study of the Christian Church 18 (2-3) (2019) 132-145