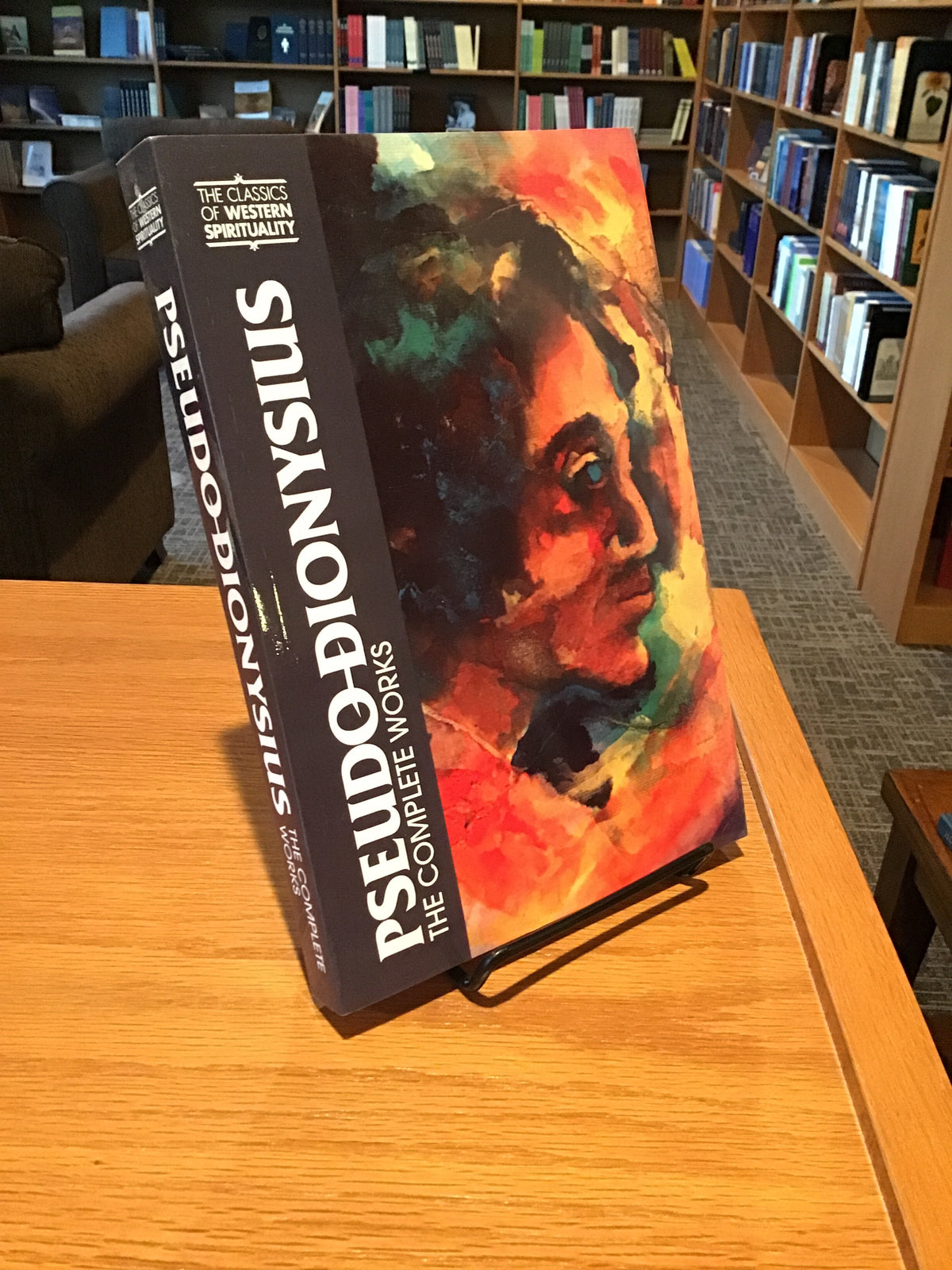

We have now finished Aidan Hart’s book on Festal Icons. From next Thursday (31 October) we will start to read “The Mystical Theology” section from The Classics of Western Spirituality edition of Pseudo-Dionysius: The Complete Works.

Our Thursday morning sessions start with intercession prayer: we pray for all those who need it. We then have an informal but lively reading session with much debate and exploration of theological themes around our subject text. These reading discussions are a way for us to deepen our understanding of the Faith. All our welcome!

St. Dionysius

St. Dionysius the Areopagite was a member of Athens’ prestigious Areopagus court in the first century AD. According to the Acts of the Apostles, he was converted to Christianity by St. Paul’s preaching at the Areopagus. Prior to his conversion, he came from a distinguished Athenian family and was well-educated in philosophy.

According to tradition, after his conversion, St. Paul appointed him as the first Bishop of Athens. He travelled to Jerusalem where he met the Theotokos and was present at her Dormition. After witnessing St. Paul’s martyrdom in Rome, he embarked on a mission to Gaul (modern-day France) accompanied by a presbyter named Rusticus and a deacon named Eleutherius. There, he worked to convert the local pagan population to Christianity.

In 96 AD, during the reign of Emperor Domitian, St. Dionysius and his companions were martyred by beheading. Tradition records that after his execution, his head rolled to the feet of a Christian woman named Catula, who ensured that he received a proper burial.

The Dionysian corpus

The Dionysian corpus consists of four theological works (The Divine Names, The Mystical Theology, The Celestial Hierarchy, and The Ecclesiastical Hierarchy) and eleven letters. Modern scholarship has argued that these texts could not have been written by St. Dionysius himself. The first confirmed historical reference to them appears in 532 AD. Some scholars, including Bishop Alexander (Golitzin) of Toledo, suggest that the theologian known as Peter the Iberian may have been the actual author.

Whoever the true author may be, it is generally acknowledged that they utilised Neoplatonic philosophical language to express Christian theological and mystical concepts. While some modern Orthodox theologians like Georges Florovsky and John Meyendorff have expressed reservations about the corpus’s influence, others strongly defend it. Vladimir Lossky considers the Dionysian understanding of God’s unknowability as essential to Christian thought and as a precursor to St. Gregory Palamas’s work. Bishop Alexander views it as an authentic Christian liturgical theology. The integration of Dionysian theology into Orthodox tradition was largely accomplished through St. Maximus the Confessor and St. John of Damascus, with the latter citing Dionysius’s Letter to Titus in his iconoclasm-era defense of icons, On the Divine Images.

From the Preface to The Classics of Western Spirituality edition

“Indeed the inscrutable One is out of the reach of every rational process. Nor can any words come up to the inexpressible Good, this One, this Source of all unity, this supra-existent Being. Mind beyond mind, word beyond speech, it is gathered up by no discourse, by no intuition, by no name.”

—Pseudo-Dionysius (5th or 6th century)

There are few figures in the history of Western Spirituality who are more enigmatic than the fifth or sixth-century writer known as the Pseudo-Dionysius. The real identity of the person who chose to write under the pseudonym of Dionysius the Areopagite is unknown. Even the exact dates of his writings have never been determined. Moreover the texts themselves, though relatively short, are at points seemingly impenetrable and have mystified readers over the centuries. Yet the influence of this shadowy figure on a broad range of mystical writers from the early middle ages is readily discernible. His formulation of a method of negative theology that stresses the impotence of humans’ attempt to penetrate the “cloud of unknowing” is famous as is his meditation on the divine names.

René Roques